Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to transform society, for good and bad. For some, AI promises commercial opportunities akin to those generated by the industrial revolution and improved human welfare. Others fear automated discrimination, widespread surveillance, a decay of democracy and evaporating human autonomy. That makes effective regulation of AI a paramount challenge of our time. Nevertheless, regulatory interdependence affects how and to what degree AI ethical concerns can and will be addressed, and it lays out how a variegated approach to such interdependence is necessary to maximize jurisdictions’ AI sovereignty – a key dimension of the “digital sovereignty” the EU has explicitly set as its goal.

Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) has the potential to transform society, for good and bad. For some, AI promises commercial opportunities akin to those generated by the industrial revolution and improved human welfare. Others fear automated discrimination, widespread surveillance, a decay of democracy and evaporating human autonomy. That makes effective regulation of AI a paramount challenge of our time.

At present, the global regulatory landscape for AI has three centers of gravity: the USA, China, and the European Union. Of the three, China seems most comfortable with government(-sanctioned) use of AI to monitor and control populations. In the USA, corporations enjoy the most autonomy to use AI as they please. And the EU stands out as the jurisdiction with the highest regulatory ambitions, inspired by a vision it calls “human-centered AI.”

Scoring different approaches to AI for ethical probity is a complicated endeavor: How heavily particular concerns weigh varies. The costs and benefits of widespread AI application will be distributed unevenly throughout societies, creating both winners and losers. And, maybe most importantly, it is unclear to what degree a restrictive approach to AI also entails lost opportunities to improve human welfare. AI ethics, in other words, is a societal affair but with many personal implications.

The EU sees more need than both China and the USA to delimit the use of AI in light of ethical worries. That said, the effectiveness and substance of any jurisdiction’s AI regulation will depend heavily on developments and policies elsewhere in the world, a dynamic scholars call regulatory interdependence. What can be achieved in terms of AI-ethics, in other words, depends on what others in the field do. In that sense, no jurisdiction is an island.

Regulatory interdependence affects how and to what degree AI ethical concerns can and will be addressed, and it lays out how a variegated approach to such interdependence is necessary to maximize jurisdictions’ AI sovereignty – a key dimension of the “digital sovereignty” the EU has explicitly set as its goal. As a set of transformative technologies, AI is not only novel and idiosyncratic, but enormously varied in its applications. Much of the current debate is cast in binary terms: The EU should either defend its own approach to AI, or embrace global or transatlantic rules. Both approaches miss the mark, however, because regulatory interdependence is highly diverse. Some implications of AI – say, safety hazards from AI-powered vehicles – can be regulated unilaterally (low interdependence). Others, like non-proliferation of automated disinformation or weapons, require pro-active engagement of non-EU partners (high interdependence).

Because the EU currently has the highest regulatory ambitions, it is a useful case to investigate more specifically how regulatory interdependence impinges on its ability to attain its aims. This essay takes EU AI regulation as an exemplary case to ensure substantive consistency. Mutatis mutandis, the reasoning advanced here also applies to other jurisdictions.

To what degree regulatory interdependence limits a jurisdiction’s digital sovereignty depends on three factors: (1) the specific regulatory preferences a jurisdiction has, i.e. how restrictive it would like rules to be, (2) the size of its internal markets and (3) where its own technological development stands relative to that of other jurisdictions.

The State of Play: EU AI Regulation in the Global Context

AI has no self-evident boundaries. The Commission itself plausibly defines it as “systems that display intelligent behavior by analyzing their environment and taking actions – with some degree of autonomy – to achieve specific goals.” Sidestepping definitional debates, here we pragmatically follow this definition and thus the scope of AI regulation as it empirically emerges in the policy process.

The Commission proposal divides AI into three tiers. One category of applications is banned outright; a second swath of low-risk AI applications requires little public oversight; the third, in-between “high-risk” category receives most regulatory attention. The draft regulation outlines the approach the Commission envisions internally, i.e. within Europe.

Yet actors and experts in the AI field – public and private, European and non-European – tirelessly underline the need for cross-border cooperation. Regulatory choices elsewhere in the world shape the effects and effectiveness of EU rules. External engagement is inevitable to tackle these interdependencies and to maximize what the EU calls its “digital sovereignty.” The question at this juncture is: To what degree should the EU seek, or must it even seek, cooperation with non-EU actors to address its regulatory concerns?

The EU is currently engaged in sundry outward-focused AI-related initiatives. Their four central axes are bilateral links with China, links with the USA, multilateral regulatory efforts, and transnational private standard setting. Across the Atlantic, the USA had initially resisted formal regulatory cooperation lest it become entangled in a restrictive EU-style regime. But in 2021, the US Congress and the White House shifted gears, favoring joint AI standards “to stand up for democratic values.” In effect, the US government envisions an anti-China coalition, fearing transpacific rivalry and Chinese technological prowess. In June 2021, ongoing informal transatlantic AI-dialogues were fused in the newly established Trade and Technology Council.

For its part, China has declared AI a top priority in its latest five-year plan, promising to become a world leader by 2030. In spite of AI-powered human rights violations in the Uyghur-province Xinjiang and Communist party mass surveillance, the EU has hesitated to embrace the AI arms race logic. MERICS, Europe’s largest China-focused think tank, recently advocated a more balanced EU engagement with China on AI matters. The EU is clearly more aligned with the USA than with China, but for both parties, it is highly unclear how far cooperation and agreement on joint rules will or should go.

Meanwhile, multilateral regulatory initiatives are proliferating with strong EU support. Eight international organizations, prominently including the EU, launched globalpolicy.ai in September 2021, a platform for global standard development. The non-binding G20 principles from 2019 or the conclusions of UNESCO’s 2021 AI Summit also include countries from around the world. In contrast, in the 2020 Global Partnership on AI (GPAI), 20 “like-minded” countries plus the EU aspire to a shared vision built on democratic principles and liberal values, excluding AI-powerhouses China and Russia. At NATO’s July 2021 summit, its deputy secretary general demanded more international cooperation to counter China’s growing AI-powered military might. Truly global efforts compete with alliances of “like-minded” countries.

In parallel, essential regulatory cooperation unfolds in non-governmental bodies. The Joint Committee of the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), known as ISO/IEC JTC 1/SC 42, has been developing AI standards since 2017. Equally relevant to maturing AI technology, corporate initiatives such as the Object Management Group develop standard formats, for example, for training data sets. And global NGOs such as ACCESS NOW and the tech-industry sponsored Partnership on AI work on AI “labels,” comparable to those of the Forest Stewardship Council. It remains to be seen, however, whether such initiatives can solve regulatory conundrums below the radar of explicitly political struggles, and to what degree the EU will be able to co-opt or leverage them.

Regulatory Interdependence and Ways to Tackle It

Regulatory interdependence arises when one jurisdiction’s regulation affects that in another—especially when it limits regulatory effectiveness or creates negative externalities. We can distinguish three stylized forms of regulatory interdependence: Coordination problems, competitive dynamics, and indirect spillover. The first arise when incompatible rules impede trade flows and limit products’ interoperability. Even when jurisdictions share regulatory aims, they thus face coordination problems.

Competitive dynamics come into play when one jurisdiction desires tighter standards than others. Trade flows may be affected in both directions: Domestic producers may struggle to compete in foreign markets because of high compliance costs at home. Conversely, foreign producers may find market access limited, unless they either produce to different national specifications, or switch production to foreign standards altogether. Such limits to market access can reflect both genuine regulatory concerns and efforts to shield domestic producers from economic competition through regulatory protectionism.

Finally, jurisdictions may worry about the indirect spillovers of regulation abroad, for example when lax logging rules hasten rainforest destruction. This form of regulatory interdependence rarely figures in the economic literature about it. But it is important when – as in the case of AI – abstract normative concerns loom large. Many democratic governments fear, for example, that oppressive AI tools, developed by authoritarian regimes, proliferate around the world and thus solidify the position of autocratic rulers and empower terrorist or otherwise malign organizations.

Jurisdictions have alternative strategies to tackle regulatory interdependence. When the cross-border impact is low, one option is benign neglect. Once stringent standards affect firms’ competitiveness, however, a jurisdiction may embrace regulatory competition and dilute its rules to benefit local firms. Or it may accept mis-matched standards and sacrifice trade openness to safeguard regulatory goals or protect domestic producers.

Dynamics shift when a large jurisdiction can leverage access to its market as a power source. It can then force others to tighten regulations to avoid competitive disadvantage. The EU has often exercised such “market power,” externalizing its policies both consciously and unintentionally.

Alternatively, jurisdictions can cooperate to sidestep regulatory competition and solve coordination problems. Formats vary from international trade agreements, via trans-governmental networks, to the implicit endorsement or embracing of privately set standards, each with their own advantages and drawbacks.

Barring multilateral arrangements, the EU in particular has frequently embraced or even orchestrated standard setting by private actors, for example in sustainability. Such approaches are particularly attractive when global firms constitute the heart of an economic sector, and when tapping their expertise bolsters regulatory effectiveness. At the same time, jurisdictions often hesitate to relinquish control completely, e.g. in accounting standard setting. Private standards can lack effective enforcement, and observers have often worried about regulatory capture when private actors take too prominent a role in rule setting. Scholars therefore continue to debate whether private standards can be more than second-best alternatives to legally enshrined rules.

Where harmonized standards are beyond reach, mutual recognition of local rules can facilitate cross-border market access. It has been a cornerstone of the single European market, but has also been used to manage transatlantic regulatory interdependence, including in the technically complex field of finance.

In theory, then, these are alternative approaches to tackling regulatory interdependence:

| Approach to tackling regulatory interdependence | Characteristics |

| Benign neglect | Appropriate if both economic costs are low and regulatory effectiveness does not suffer |

| Regulatory competition | Sacrifices regulatory stringency to benefit of domestic firms in international competition |

| Regulatory concessions | Sacrifices regulatory goals when foreign firms and products are without alternative and there is insufficient leverage to enforce higher standards |

| Regulatory protectionism | Erects barriers to trade to keep out products that do not fulfil regulatory standards; can entail competitive disadvantages for domestic firms and limits (as intended) product availability on domestic markets |

| Externalization of domestic rules, intentionally or otherwise | Works well if entry to domestic market is attractive for foreign firms and rule compliance can easily be monitored |

| Push for international standards | Typically requires consensus among and an alliance of jurisdictions strong enough to set market rules |

| Embrace of transnational private standards | Second-best option when international standards fail; useful when like-minded firms dominate a sector globally; entails risk of regulatory capture |

| Mutual recognition of foreign standards | Useful for accommodating per-country idiosyncrasies in regulatory regimes that have comparable levels of stringency, creating a level playing field |

How AI is Special

One characteristic that makes AI special is the enormous breadth of applications. Regulation with an eye to ethics thus concerns how it can be developed (for example what kind of data algorithms can be trained), how it can be used, and how it can be traded, for example to keep it from falling “into the wrong hands.” Jurisdictions may find themselves agreeing on the restrictions for some uses, and disagreeing for others. We should therefore not expect jurisdictions to agree or disagree across the board. Instead, there is a variegated landscape with different degrees of international disagreement across different issues.

Ex ante, in this constellation of preferences, jurisdictions may find it easy to cooperate on some issues and hard on others. Also, the costs of non-cooperation, particularly in regulatory dimensions, are bound to vary widely. It therefore makes sense to conceive of international cooperation in AI regulation as a differential affair: Different approaches for different dimensions.

Take the concrete example of scoring algorithms, for example, for loan applications, university applications, or jobs. Such scoring can be automated, but people rightly worry about hard-to-detect patterns of discrimination in the assigned scores, and have called for regulatory safeguards. Here, the EU and the USA, for example, might agree on the appropriate level of safeguards for scoring university applications, but might disagree insofar as loans are concerned. There is no overriding reason preventing the two jurisdictions from having a shared standard (say, an open transatlantic market) for the former, and regulatory barriers and a more segmented market for the latter.

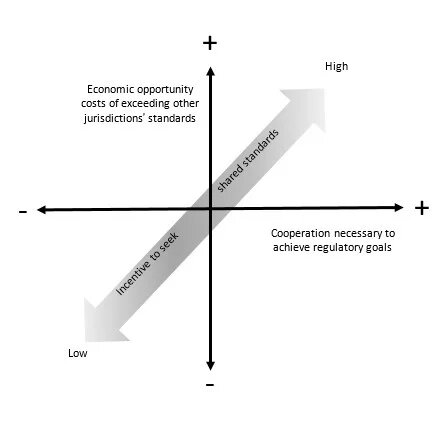

(Economic opportunity costs of exceeding other jurisdictions’ standards)

This logic extends to other kinds of ethical concerns in AI diplomacy: Some aspects of AI regulation might be covered by international regimes, because legislating them unilaterally may be unfeasible; others may be governed by smaller groups of like-minded countries, or by a jurisdiction on its own. Overall, what is called for to maximize the overlap between rules in place and the ethical goals is a variegated policy, not an approach that asks whether a jurisdiction such as the EU is either with the US, or adopts global rules, or crafts its own. It should do all at the same time, depending on the regulatory concern in question.

To make the bewildering array of ethical concerns tractable, the simplifying framework in Figure 1 links regulatory concerns to two central dimensions of regulatory interdependence. The first, on the horizontal axis, concerns the degree of cooperation necessary to achieve regulatory goals;the second, on vertical axis, captures the economic (opportunity) costs of exceeding other jurisdictions’ standards. Where regulatory concerns fall along the two axes depicted in Figure 1, depends on their specific characteristics. Figures 3 and 4 highlight factors relevant to the two axes:

Cooperation necessary to achieve regulatory goals

In principle, unilateral regulation is relatively easy and effective when it concerns:

- Use of AI-powered hardware in home jurisdiction (e.g. self-driving cars)

- Application of AI by domestic firms for specific uses (e.g. loan scoring by domestic banks)

- Corporate liability for malfunctioning AI (e.g. defective “smart home” appliances)

It is harder when concerns are about:

- Indirect spillover from AI-use elsewhere (e.g. automated weapons systems deployed abroad or political oppression)

- Verification of how AI was developed (e.g. use of illegitimate training data)

- Verification of AI use in services supplied from abroad (e.g. use of social media)

Economic opportunity cost of exceeding other jurisdictions regulatory standards

In the AI field, such economic opportunity costs can in principle arise in five dimensions: for domestic technology firms, for domestic firms in other sectors, with respect to economic growth, regarding widening inequality in society, and in expected job losses due to automation. The opportunity costs are relatively low for

- AI-powered products that can easily be customized to local regulatory requirements (e.g. self-driving cars)

- Requirements that impose equal costs on domestic and foreign producers (e.g. requirement that AI-driven decisions be explainable to customers)

They are relatively high, in contrast, for example for

- Prohibitions of AI applications that dent competitiveness of local producers globally (e.g. banks forbidden to use AI for stock trading)

- When there is a high cost to fulfilling specific regulatory requirements in the development of freely tradable AI products (e.g. demanding rules for securing individuals’ consent to share their medical data)

If a particular regulatory concern scores highly on either of those dimensions, and a jurisdiction finds itself favoring higher standards than main competitor jurisdictions, it has an incentive to seek shared standards. In principle, global rules are preferable to bilateral ones to avoid market fragmentation, regulatory competition, and negative externalities. But if regulatory preferences diverge highly around the globe while the EU finds itself aligned with specific partners, bilateral cooperation is an obvious path to choose. In addition, where standard development is highly technical and the costs of standard creation loom large, it becomes attractive to outsource it to technical experts in transnational non-governmental organizations, or to delegate it to intergovernmental forums with few active participants. The same is true for standards that require frequent updating because of technologies’ dynamism, which is difficult for detailed international agreements. Finally, where high regulatory capacity is essential for cooperation, for example to ascertain the equivalence of foreign compliance monitoring regimes, participating in cooperative efforts may be limited to jurisdictions capable of enforcing hard-to-monitor rules.

Implications for Jurisdictions of Different Sizes and with Different Regulatory Preferences

The framework outlined above allows us to map specific regulatory concerns along the two main axes identified and to establish to what degree international regulatory cooperation is necessary to address regulatory concerns and hence maximize digital sovereignty. To what degree are these considerations transferrable to other jurisdictions?

Jurisdictions with high regulatory demands but smaller markets will have a harder time safeguarding their own digital sovereignty. Their markets may be too small to allow the growth of a domestic AI sector beholden to local rules, and international firms my be unwilling to tailor their products to the specifications of small jurisdictions. The economic opportunity costs are thus higher. The most obvious route for these jurisdictions to take would be to form a coalition with, or bandwagon behind, other large jurisdictions with a regulatory philosophy close to their own – at least on specific issues. This dynamic might create a coalition of the willing around the EU, for example.

At the other end of the spectrum, large jurisdictions with relatively few regulatory concerns will not entirely escape the impact of regulatory interdependence. They, too, confront coordination problems – for example, about the interoperability of AI systems – that may restrict global market access. Here, all jurisdictions have an incentive to cooperate, but particularly those whose level of technological development would make them a natural winner on the global scale if market access were unimpeded. China and the USA thus have much to gain from global standards that facilitate the global spread of their domestic firms.

At the same time, in the struggle for global dominance in this field, both the USA and China will want to draw other countries into their regulatory orbits. Being courted from multiple sides in turn gives also second-tier AI powers a bit of leverage. The complicated global constellation of interests and preferences means that the future outcome is still highly uncertain. At the same time, appreciating the ways in which variegated regulatory interdependence creates opportunities for selective engagement with other major AI powers is a key prerequisite for maximizing digital sovereignty in a globally connected world.

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Tel Aviv and/or its partners.