The Middle East is and will be one of the region’s most severely affected but least equipped to deal with the effects of climate change. The climate crisis is known to be a threat multiplier, exacerbating existing conflict drivers in the water-scarce region, and posing new challenges to already fragile and little resilient states. The impacts of climate change continue to escalate whilst the insufficient capacity to cope with and adapt to its effects undermines national security and stability. Governments across the Middle East have so far done little to mitigate these effects, even though actions are urgently required to prevent further destabilization.

As the implications of climate change for security and stability transcend political and national borders, actions and solutions require a collaborative effort. The climate crisis, thereby, forces non-traditional partners to cooperate and could present opportunities to overcome historic grievances, promote trust-building and improve relations between Israel and its Arab neighbors through economic and environmental cooperation. By encouraging regional cooperation to improve the adaptive capacities of all countries, climate change could, thus, also serve as a multiplier of opportunities.

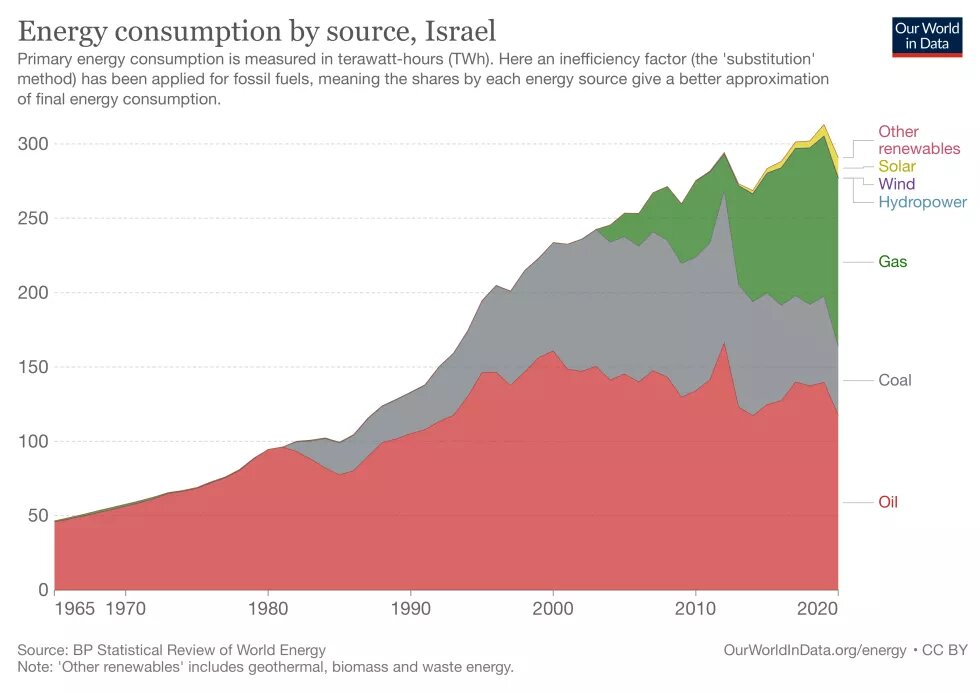

With vast desert tracks, lots of solar rays and access to new and efficient power generation and storage technologies, Israel’s solar energy potential is ample. Nonetheless, only 8 percent of its electricity is currently sourced from solar power (Agencies, 2021). Hurdles include the country’s insufficient and outdated electric infrastructure as well as the lack of land resources. (Israel Country Commercial Guide: Energy, 2022; Surkes, 2021).

Striking example of cross-border cooperation: the water-for-energy deal

In 2021, Israel, Jordan and the United Arab Emirates (UAE) signed a Declaration of Intent (DoI) for an exemplary climate cooperation project: the water-for-energy agreement. The goal of the project, described as a “success story on paper” (Van Zuiden, 2021), is to broker exchange of desalinated water and solar energy between Israel and Jordan (Mahmoud, 2021; Münch & Schröder, 2021). The initiative serves as an example of cooperation between non-traditional partners in the climate-water-energy field and could become a pilot for similar projects in the future.

The signing parties recognize “the need for regional cooperation to meet the challenges posed by the climate crisis on water and security” (Declaration of Intent, 2021). If successful, the initiative could showcase how climate change and economic interests open doors for enhanced cooperation between former adversaries.

The DoI is especially interesting, because despite the existence of a peace treaty, relations between Israel and Jordan have always been highly strained since Jordan is the Arab state most closely connected to the Palestinians and the Israeli-Palestinian conflict with more than half its population having Palestinian heritage or being Palestinian refugees. The Jordanian public is, therefore, known for strongly opposing any cooperation with Israel. Consequently, the negotiations on the new agreement have provoked protests and walkouts of parliament in Amman.

The water-for-energy deal was reportedly first discussed in a meeting between the UAE’s Ambassador to Israel Mohammed Al Khaja and Israel’s former Energy Minister Karine Elharrar in September 2021. Roughly a year after the Abraham Accords were signed in 2020, the initiative was considered as a possibility for the UAE to help Israel arrange further agreements with other Arab states and to address the challenges climate change poses to the region (Staff Reporter, 2021).

The inspiration behind the initiative came from EcoPeace Middle East, a regional NGO, which suggested a water-energy cooperation as part of their proposed “Green Blue Deal for the Middle East” (Bromberg et al., 2020; EcoPeace Middle East, n.d.). The project suggestion, however, also included the Palestinian Authority as a third party to the deal - an aspect that has not been implemented in the new initiative. EcoPeace’s plan aimed to offer a solution to the effects of climate change on the region, combat water scarcity and create conditions for peace in the Middle East, thereby, effectively laying the groundwork for the new initiative (Bromberg et al., 2020; Deutsche Welle, 2022).[1]

The landmark cooperation agreement consists of two contingent and independent components (Ministry of Energy, 2021):

The first component, “Prosperity Green” relates to the construction of a solar power and energy storage plant, which is to be built in the Jordanian desert by Masdar, a government-owned company from the UAE (Deutsche Welle, 2022; Münch & Schröder, 2021). The major Jordanian solar plant is to reach a capacity of 600 megawatts annually and shall, possibly by 2026, supply green electricity to Israel at a cost of $180 million per year (Mahmoud, 2021; Münch & Schröder, 2021), helping Israel to bolster its renewable energy portfolio. The profit is to be split between Jordan and the Emirati company Masdar.

In return, Jordan shall be provided with urgently needed desalinated water, up to 200 million additional[2] cubic meters annually, most likely from a new coastal desalination facility in Israel (Ministry of Energy, 2021). This additional water supply represents the second component of the agreement, “Prosperity Blue”, and could help Jordan address its severe water scarcity.

The resource swap is made feasible by the fact that both countries have access and the ability to produce one of the two resources (Simon, 2021; Van Zuiden, 2021).[3] The Director of EcoPeace Israel explains the mutually beneficial resource swap: “For the first time, all sides have something to sell and something to buy” (Al Jazeera, 2021). Supporters hope that the unprecedented alignment of interests could simultaneously help to repair the semi-fractured relations between the neighbors (Simon, 2021).

After months of secret negotiations, the DoI was signed by the responsible ministers of both countries, Jordan’s Water Minister Mohammed Al-Najjar, former Israeli Energy Minister Karine Elharrar, and the Emirati Special Climate Change Envoy and Minister of Industry and Advanced Technology Sultan Ahmad Al Jabar at the Dubai Expo in November 2021 (Harkov, 2021). US Special Climate Change Envoy John Kerry and the Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed were also present at the signing ceremony, reflecting the countries’ major role in the conclusion of the deal (Mahmoud, 2021). Despite this important DoI, the project itself will probably still require about a decade to become fully operational (della Ragione & Eran, 2021).

Next steps: implementation plans

Critical in terms of the deal’s success or failure are feasibility aspects which need to be addressed before the proposal can eventually be transformed into reality. At the COP27 climate summit in Sharm el-Sheikh, the parties signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) to move ahead with the cooperation after initial assessments, focusing on logistical, economic, regulatory and technical aspects of the cooperation had found the project to be feasible (Reuters, 2022). In a next step, implementation plans shall be developed in time for COP28 hosted by the UAE in November 2023. However, the signed DoI and MOI so far do not contain any legal obligations, negotiations on a final, binding agreement remain in a preliminary state and opinions differ on whether the agreement will eventually be finalized.

Timing: why was the Declaration of Intent suddenly signed?

The question arises why the cooperation initiative was suddenly rendered possible, even though the project was already suggested by EcoPeace several years ago, bilateral relations between Israel and Jordans were described as “at an all-time low” by the Jordanian King in 2020 and Israel’s interest seemed to be shifting away from Jordan and Egypt towards the Gulf.

On the Israeli domestic level, national security considerations related to the potential instability of its neighbor Jordan as well as to the effects of climate change on Israel and the region played an important role in the conclusion of the negotiations. In addition, the understanding that the agreement could help Israel meet its proclaimed climate change commitments facilitated the negotiation’s success.

For Jordan, one of the most water-scarce country in the world, additional supply of water played a tremendously important role and was complemented by the significant economic benefits of the agreement due to the sale of solar energy as well as the possibility to position itself as a regional hub for renewable energy. However, the Jordanian public’s opposition to cooperation with Israel, manifesting in large protests in Amman, hindered the conclusion of the deal.

The involvement of the UAE as a third-party and as a mediator facilitated the negotiations and made the cooperation possible. For the UAE, the deal is an opportunity to promote their role as a peacemaker and mediator between Israel and other states in the region, thereby securing support from the USA, to increase their geopolitical relevance as well as to gain regional leadership on climate and sustainability topics.

Bilateral level - A basis for healthy interdependencies?

On a bilateral level, the agreement has been applauded as an important foundation for improved relations between Israel and Jordan and described as heralding a new period of warm peace based on mutual interests and interdependencies. If successfully concluded, the deal would be one of the largest cooperation initiatives between the countries since Israel and Jordan signed their peace treaty 28 years ago (Davis, 2021). However, tensions, imbalances and economic power disparities between the parties continue to exist and pose challenges to their fragile relationship. Factors such as larger anti-normalization protests in Jordan, a deterioration of relations between Amman and the new Israeli right-wing government or a sudden spike in violence in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict could potentially hamper the success of the project. Thus, diverging views exist on the future impact of the initiative on a bilateral level.

The agreement could help to build healthy interdependencies between the countries and open up opportunities for further cooperation and enhanced trust, now that the relationship between the administrations has potentially been stabilized during the term of the last Israeli government. However, additional steps such as cooperation on a citizen level must follow to build long lasting ties. If successfully concluded, the cooperation could reinforce the riparian states common climate, economic and security interests and boost joint climate actions. Experts further claim that the deal could alleviate Jordan’s acute water shortage and contribute to more effectively combatting climate change in the future (della Ragione & Eran, 2021).

Nonetheless, and despite high hopes, experts remain cautious and point to persisting political obstacles for the relationship, among which Jordan’s close connection to the Palestinian cause as well as the new Israeli government rank highest. Jordanian-Israeli ties have always been highly fragile and easily influenced by incidents related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and changes in high-level officials.

The election of Israel’s new far-right government led by former Prime Minister Netanyahu has sparked regional concerns and could deteriorate the relations between Israel and Jordan (Keinon, 2023). While Israel’s new government has expressed its desire to proceed with the previous administration’s efforts to advance regional integration, this may not be possible if it simultaneously jeopardizes the status-quo in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict by disregarding previous arrangements (Magid, 2023). Given the far-right composition of the Netanyahu administration as well as its actions vis-à-vis the Palestinians, cooperation initiatives with other Arab states such as the water-for-energy cooperation may be put on hold or worse.

Israel’s national security minister Itamar Ben-Gvir’s provocative visit of the Al-Aqsa Mosque compound and the condemnation that followed from Jordan, the UAE and other Arab states is a first example of the new government’s potential damage to Israeli-Jordanian and Israeli-Arab ties. Consequences of Ben-Gvir’s actions already include the postponement of Prime Minister Netanyahu’s visit to the UAE as well as Amman summoning the Israeli ambassador. Thus, time will tell if the composition of the current government will become an obstacle to the success of the new deal by itself.

Intersecting economic interests might not prove sufficient to significantly improve the Israeli-Jordanian relationship, reduce tensions or induce real political consequences. Instead, some experts opine that the current strategy of economic peace will only be sustainable if complemented with a feasible solution for the omnipresent Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Benefits of economic cooperation will be limited as long as they are not embedded into a larger political process which involves an end to the Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories (Simon, 2021). Following this, it remains to be seen whether future cooperation between Israel and Jordan will be possible or be met with even stronger opposition from the Jordanian population.

Potential avenues to complement the current initiative with a Palestinian component and secure Palestinian water rights, as originally suggested by EcoPeace, need to be explored for a long-lasting success of the project and for Israeli-Jordanian relations to improve sustainably. Whilst healthy interdependencies and trust are most difficult to build, they are also the most enduring once in place and could present an important pillar of lasting security and peace for the Middle East.

Regional level - A pilot project for further cross-border cooperation initiatives in the Middle East?

On a regional level, the DoI is an important development because of two main reasons: first, it is considered a model for out-of-the-box-thinking on joint climate change mitigation in the Middle East and, secondly, it could incentivize further regional cooperation in the future (Deutsche Welle, 2022; Münch & Schröder, 2021). As the effects of climate change become increasingly visible in the Middle East, the deal could turn out as a pilot project of climate cooperation. Its success may encourage other countries in the region to partner in similar resource cooperation initiatives (Munayer, 2020). If successful, the agreement could showcase how the climate crisis can present an opportunity to overcome historic grievances, promote confidence building and collectively address environmental challenges.[4] The initiative could contribute to a paradigm shift in the perception of resource scarcity by highlighting that climate change can also offer possibilities for cooperation. Much depends, however, on whether real implementation of the project will follow.

In addition, the new deal sheds light on a regional trend that has become visible since the conclusion of the Abraham Accords: Cooperation with Israel is no longer dependent on a solution in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict as previously demanded by the Arab Peace Initiative. Instead, a slow process of the Palestinian cause losing its relevance for the Arab states is observable with countries formerly opposing cooperation now normalizing ties with their former enemy. The economic benefits of cooperation with Israel highlighted by the new initiative may motivate other Arab states to intensify cooperation despite a lack of progress in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The agreement may, thus, serve as an example of the role economic cooperation can play in facilitating the transition towards closer cooperation between former enemies. The assumption that economic development through economic cooperation will lead to political stability in the region is also one of the main premises behind EcoPeace’s Green-Blue deal (Yasuda et al., 2017, p. 81).

Whilst some experts argue that increased economic interdependencies can be used by Arab states as leverage in effectuating a solution between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, the political will to do so does currently not seem to exist. Instead, a trend of Palestinians increasingly being perceived as a burden and an obstacle by their former Arab allies is observable.

Climate change – creating opportunities for cooperation

To conclude, climate change will continue to impact the Middle East severely. Finding possibilities to jointly address and combat the climate crisis will be necessary to reduce the severity of these effects. This article aimed to contribute to raising awareness for the challenges that lay ahead and shed light on an exemplary cooperation initiative in the field which might provide insights for similar projects in the future. As water and energy continue to gain geopolitical relevance, it is necessary to highlight the potential for cooperation that lays in resource scarcity and climate change, instead of solely pointing out the challenges.

Sources

Agencies. (2021, April 3). Israel aims to become world leader in use of solar energy. The Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202104/1220151.shtml

Al Jazeera. (2021, August 31). Drought diplomacy boosts Israel-Jordan ties. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/8/31/drought-diplomacy-boosts-israe…

Al-Juneidi, L. (2021, October 12). Jordan to buy 50 million m3 of water from Israel. Anadolu Agency. https://www.aa.com.tr/en/middle-east/jordan-to-buy-50-million-m3-of-wat…

Bromberg, G., Majdalani, N., & Abu Taleb, Y. (2020). A Green Blue Deal for the Middle East (pp. 1–26). EcoPeace Middle East. https://ecopeaceme.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/A-Green-Blue-Deal-for…

Davis, H. (2021, November 26). Hundreds protest in Jordan against water-energy deal with Israel. Al Jazeera. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2021/11/26/hundreds-protest-in-amman-aga…

Declaration of Intent between the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan, the State of Israel and the United Arab Emirates. (2021). https://www.gov.il/BlobFolder/news/press_221121/en/DOI_221121.pdf

della Ragione, T., & Eran, O. (2021, December 1). Include Palestinians, EU in Israel-Jordan water-energy deal. The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/opinion/include-palestinians-eu-in-israel-jordan-…

Deutsche Welle. (2022). Israel and Jordan’s climate deal: Water-for-energy swap. Frontline. https://frontline.thehindu.com/dispatches/israel-and-jordan-climate-dea…

EcoPeace Middle East. (2017). Water-Energy Nexus Pre-feasibility study. EcoPeace Middle East, Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. https://old.ecopeaceme.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Water-Energy-Nexu…

FAO. (n.d.). Water Scarcity. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/land-water/water/water-scarcity/en/

Ghazal, M. (2022, July 17). Nearly empty dams foretell a worrying year for Jordan’s water sector. The Jordan Times. https://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/nearly-empty-dams-foretell-worry…

Gorelick, S. M., Yoon, J., & Klassert, C. (2021, March 29). Avoiding crisis in Jordan’s tenuous water future. Climate-Diplomacy. https://climate-diplomacy.org/magazine/conflict/avoiding-crisis-jordans…

Harkov, L. (2021, November 17). Israel, Jordan to sign UAE-mediated energy and water agreement—The Jerusalem Post. The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/israel-jordan-to-sign-uae-mediated-en…

Israel Country Commercial Guide: Energy. (2022). US International Trade Administration. https://www.trade.gov/country-commercial-guides/israel-energy

Israel: Health and Climate Change Country Profile 2022 (WHO/HEP/ECH/CCH/22.01.06; Health and Climate Change Country Profile 2022). (2022). World Health Organization; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/352628/WHO-HEP-ECH-CCH…

Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs. (1994). Israel-Jordan Peace Treaty. https://mfa.gov.il/mfa/foreignpolicy/peace/guide/pages/israel-jordan%20…

JT. (2022, July 21). Renewables accounted for 26% country’s energy production in 2021—Energy Ministry. The Jordan Times. https://www.jordantimes.com/news/local/renewables-accounted-26-countrys…-—-energy-ministry

Kapetas, A. (2022, February 16). Water-for-energy deal could help prevent climate conflict in the Middle East. The Strategist. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/water-for-energy-deal-could-help-prev…

Keinon, H. (2023, January 11). Why don’t Israelis care about the Negev Forum? - Analysis. The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/middle-east/article-728259

Magid, J. (2023, January 8). US laments Jordan’s absence from Negev Forum, aims to keep Palestinians in loop. The Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/us-laments-jordans-absence-from-negev-for…

Mahmoud, M. (2021, December 16). Exploring the feasibility of the Jordan-Israel energy and water deal. Middle East Institute. https://www.mei.edu/publications/exploring-feasibility-jordan-israel-en…

Ministry of Energy. (2021, November 22). UAE, Jordan and Israel collaborate to mitigate climate change with sustainability project. Ministry of Energy. https://www.gov.il/en/departments/news/press_221121

Ministry of Water and Irrigation. (2016). National Water Strategy 2016-2025. Ministry of Water and Irrigation. https://www.pseau.org/outils/ouvrages/mwi_national_water_strategy_2016_…

Munayer, R. (2020, December 8). Navigating a Green Blue Deal for the Middle East. Climate Diplomacy. https://climate-diplomacy.org/magazine/cooperation/navigating-green-blu…

Münch, P., & Schröder, T. (2021, November 22). Jordanien und Israel: Solarstrom gegen Wasser. Süddeutsche Zeitung. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/jordanien-israel-solarstrom-1.54702…

Odenheimer, N. (2017, May 13). Israel—A regional water superpower. The Jerusalem Post. https://www.jpost.com/magazine/a-regionalwater-superpower-484996

Reuters. (2022, November 8). Israel and Jordan move forward with water-for-energy deal. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/business/cop/israel-jordan-move-forward-with-wa…

Ritchie, H., Roser, M., & Rosado, P. (2022). Energy [Online Resource]. OurWorldInData.Org. https://ourworldindata.org/energy/country/israel

Simon, B. (2021, August 31). Israel-Jordan ties boosted by rare alignment in interests on water, energy. The Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-jordan-ties-boosted-by-rare-alignm…

Staff Reporter. (2021, November 22). UAE plays key role as Jordan, Israel to collaborate for sustainability projects. Khaleej Times. https://www.khaleejtimes.com/uae/uae-plays-key-role-as-jordan-israel-to…

Surkes, S. (2021, October 20). The sun is shining, so why isn’t Israel making hay of its solar energy?. The Times of Israel. https://www.timesofisrael.com/the-sun-is-shining-so-why-isnt-israel-mak…

UN-ESCWA, & BGR. (2013). Inventory of Shared Water Resources in Western Asia: Jordan River Basin. United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia; Bundesanstalt für Geowissenschaften und Rohstoffe. https://waterinventory.org/sites/waterinventory.org/files/chapters/chap…

Van Zuiden, M.-M. (2021, August 31). From Land for Peace to Energy for Water [Newsblog]. The Times of Israel. https://blogs.timesofisrael.com/from-land-for-peace-to-energy-for-water/

Visser, Y. (2022, January 25). Analysis: How Israel Will Finally Solve Its Water Problem. Israel Today. https://www.israeltoday.co.il/read/analysis-how-israel-will-finally-sol…

Whitman, E. (2019). A land without water: The scramble to stop Jordan from running dry. Nature, 573, 20–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-019-02600-w

Yasuda, Y., Schillinger, J., Huntjens, P., Alofs, C., & de Man, R. (2017). Transboundary Water Cooperation over the lower part of the Jordan-River Basin: Legal Political Economy Analysis of Current and Future Potential Cooperation. The Hague Institute for Global Justice. https://climate-diplomacy.org/sites/default/files/2020-10/Water%20Diplo…

[1] EcoPeace has not only been advocating for a cross-border climate security approach between Jordan, Israel and

Palestine for years, but has also been instrumental in providing advocacy support and research for the negotiations

between Jordan, Israel, and the UAE (Kapetas, 2022).

[2] Israel already supplies Jordan with 45 million CM of water annually according to the terms of the countries‘ peace

Treaty (Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 1994, Chapter Annex II, Article 1; UN-ESCWA & BGR, 2013, l. 170f.).

The peace treaty further regulates water allocation and storage of the Jordan and Yarmouk Rivers. In addition,

Jordan can purchase additional quantities of water and an agreement to purchase 50 million additional CM of

water was reached in 2021 (Al-Juneidi, 2021).

[3] Unlike Israel, the Hashemite Kingdom has ample land to build solar-generating plants, plus land and labor costs

are lower, while Israel’s technological know-how and access to the Mediterranean permits direct desalinated

water conveyance to Jordan’s populous northern cities (Mahmoud, 2021).

[4] However, the agreement also faces criticism from environmental experts questioning its usability in the energy

and water security context and highlighting that many more sustainable and effective methods exist to alleviate

Jordan’s water scarcity (Davis, 2021).