This backgrounder aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of how digital media are shaping democracy and what might be done to limit possible avenues of anti-democratic abuse, while kindling their democratic potential.

1. Introduction

“This [the Internet] is where democracy happens now and there is no going back. […] If we want to make democracy better, this is what we have to tackle.” – Helen Margetts

In many Western democracies, radical and extreme right-wing and reactionary forces seem to be on the advance or held back only with the greatest effort (de Vries & Hobolt, 2020; Mudde, 2009). The culprit for these developments is usually quickly identified – it is, so the legend goes, the rise of the Internet and social media. In the past, especially leftist and liberal thinkers and movements saw the Internet as a catalyst for democracy and freedom. Today, the majority opinion is the opposite: Worries about foreign propaganda interventions, disinformation, ‘echo chambers’ and ‘social bots’ have replaced the dream of a networked public and hopes for a new form of democracy that was envisioned.

This backgrounder aims to provide a more nuanced understanding of how digital media are shaping democracy and what might be done to limit possible avenues of anti-democratic abuse, while kindling their democratic potential. We argue that digital technologies can be powerful in enabling disruptive political turbulence, but often weak in transforming this turbulence into lasting and constructive political change. Central to this argument is the understanding that the crises Western democracies are facing are political, not digital crises. The fundamental challenge that the ongoing digitization of our life and world is posing to democratic systems is that we must find a middle ground between containing the authoritarian potential of the Internet while utilizing is democratic potential. Clearly we need to sufficiently stabilize our democratic systems and protect them against authoritarian takeover attempts (as witnessed for example in the context of the 2020 US election). At the same time, we should allow for digitally-driven pushes for legitimate change, which are rooted in real-world grievances and societal crises. To achieve such a balance, it is vital to find ways to mold and moderate this new political turbulence as channeled through digital media into constructive and lasting political participation, which addresses the underlying societal crises without leading societies into death spirals of polarization (which again, in turn, open the door for authoritarian takeover). This paper will close by presenting some possible responses to these challenges.

2. How the Internet Does and Does Not Transform Politics

How does the rise of the Internet shape the public arena, or public sphere, and consequently politics? This section argues that the key consequences of the digital transformation of the public arena are the disruption of established power structures and the potential for increasing political turbulence. This turbulence is not rooted in the Internet, but in fundamental political crises and social cleavages, such as immigration, globalization, climate change, and rising inequality. However, the changes introduced by the Internet contribute to it. In what follows, we outline the key concepts, findings and arguments that are necessary to understand this development. First, we describe on a general level how the rise of the Internet has changed power dynamics within the public arena. Second, we highlight three essential consequences of this digital transformation: The easier rise of political outsiders, a greater salience of extreme voices and the amplification of conflict. Third, we elaborate how the changes introduced by the Internet relate to other factors that shape politics. Finally, we join the insights to make the general argument of the section which is, as outlined above, that the key consequences of the digital transformation of the public arena are the disruption of established power structures and the potential for increasing political turbulence.

The emergence of the Internet is transforming the logic and structure of the media and therefore the logic and structure of the public arena. Formerly characterized by the old pre-Internet mass media logic, with the rise of digital media, traditional mass media and “newer” digital media now interact and compete with each other and are emerging into a new “hybrid media system” (Chadwick, 2013).The Digital Transformation of the Media and Politics

What does the end of the mass communication era and the emergence of this new hybrid media system mean for politics? To answer this question, it is essential to first understand the logic and structure of both its parts. The old mass media logic is usually described as one-way and top-down communication, where information selection and production is dominated by elites like journalists, politicians and various civil society actors. The traditional media and its members act as central information distributors to the public, putting them in a strong position as gatekeepers of information (Chadwick, 2013; Klinger & Svensson, 2015; Van Aelst & Walgrave, 2016). With digital media, however, we have seen the emergence of a so-called “network media logic” and a many-to-many communication environment where the costs of producing and distributing information have been lowered, opening it up to new actors. Information is increasingly filtered through interpersonal connections in real time, with social networks and search engines (and their various algorithms) acting as technical intermediaries (Klinger & Svensson, 2015; Thorson & Wells, 2016). As a result of these developments, we have seen a dramatic information profusion, which, together with economic pressures on traditional media companies due to an erosion of their funding base (Nielsen, 2019) has led to a fierce competition for the attention of audiences in the digital space (Klinger & Svensson, 2015).

As indicated above, both logics interact with and influence each other. It is this “hybrid” nature of the new media system which translates the partial democratization of information brought about by digital media into a shift of power within the public arena and, potentially, in the political system as well. Looking at the new power relations within this hybrid media system, we see a large number of contributors, old and new, including traditional media , alternative media such as digital-born news outlets and partisan news outlets, political parties and actors, assorted interest groups, companies, and various members of the public to name just a few (Jungherr et al., 2020). Traditional media actors remain in a dominant and powerful position (Klinger & Svensson, 2015) but are increasingly influenced by and competing with these newly empowered actors (Jungherr et al., 2020).

In addition to these old and new elites, audiences and particularly active citizens who engage with political content online (i.e. comment, share and like – incidentally, only a subgroup of Internet news consumers actively engage) play a central role in the new hybrid media system. Their accumulated activities shape the networked digital information distribution, provide central measurements of success for audience reach and provide feedback and commentary for old and new elites (Bail, 2021; Jungherr et al., 2020). As a result of the influence of new digital elites as well of these digitally active citizens and audiences in general, former mass media elite privileges of agenda setting and framing evolve into networked agenda setting and framing, not only within digital media but within the media system as a whole (Bennett & Pfetsch, 2018).

In summary, the Internet has re-shaped the public arena in that it has led to a democratization in content contribution and distribution, combined with the real-time aspect of digital communication. Information flows have never been faster and less controllable than they are in the digital age. The question is what does this all mean for the political space?

First Implication: A Maneuver Space for Political Outsiders

The first major implication of the digital transformation of the public arena for politics is that the Internet has emerged as a central maneuver space for political outsiders. The Internet's potential to allow people to reach each other more easily, learn about the concerns of other citizens, and organize collective action, potentially resulting in large-scale political protest movements, has substantially contributed to its capacity to act as a disruptive political tool. Digitally enabled “micro-donations” of time and effort to political causes can generate chain reactions and large online- and offline mobilizations, without necessarily relying on pre-existent leadership or strong organizational structures (Margetts et al., 2016). And while many of these efforts fail, in some cases, frustration with certain issues can quickly escalate into a political storm. With so many factors contributing to such situations, eruptions are hard to predict and calculate. While such mobilizations can cause substantial turbulence, most are not particularly sustainable. The success of Podemos and Black Lives Matter on the left and Donald Trump and the German AfD on the right, however, show that the Internet in some cases has contributed to the lasting establishment of influential political actors and movements within the political landscape, actors who have challenged and continue to challenge the political status quo (Zhuravskaya, E. et al., 2020; Mundt & Bunnett, 2018; Jungherr, Schroeder, & Stier, 2019).

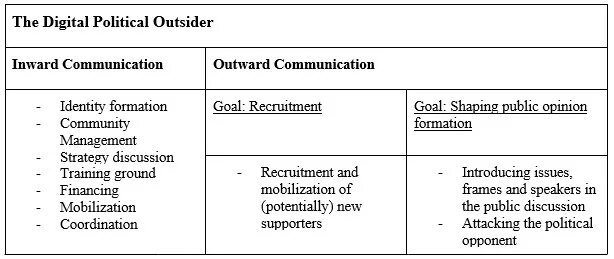

Table 1: The Digital Political Outsider. Self-created table. Developed based on Kaiser & Rauchfleisch (2019), reworked and extended based on Miller-Idriss (2020) and Rieger et al. (2021).

A key question in this context is how, exactly, political outsiders utilize digital media. In a nutshell, the Internet fulfills a number of central functions for political outsiders, which can be roughly divided into inward communication and outward communication based on (Kaiser & Rauchfleisch, 2019)[3] (see Figure 1): Inward communication comprises the communication of different actors and supporters of the political outsider with and among each other. Here we see that the Internet offers actors of varying ideological characteristics and origins the opportunity to form alliances and new movements and to exchange information across locations and contexts. Digital media are central for building relationships and communities, forming a shared identity, discussing ideology and strategy, involving supporters in training and education activities, mobilizing and coordinating them for on- and offline action and mobilizing financial resources as a funding base for these activities (Kaiser & Rauchfleisch, 2019; Miller-Idriss, 2020, Tufekci, 2017). This inward communication forms the basis for collective action aimed at outward communication.

The central goals of outward communication are, as the name suggests, more outwardly focused. Outward communication seeks to reach new supporters and to recruit and mobilize them (i.e. successful integration into the inward communication described above) (Kaiser & Rauchfleisch, 2019; Rieger et al., 2021). But aiming even further outward, it aims to shape public opinion formation in line with the political goals of the outsider. In this context, digital media are used for the introduction and amplification of issues, frames and narratives, and also for mounting political campaigns against the outsider’s political opponents (Kaiser & Rauchfleisch, 2019; Miller-Idriss, 2020; Rieger et al., 2021). It is important to emphasize that inward and outward communication cannot necessarily be distinguished from one another in practice, and moreover, an act of communication can fulfil strategic goals in both areas. For example, a group’s seemingly outward communication (e.g. addressing the political opponent) can also help it consolidate its own identity in the sense of an "us-versus-them" logic (Rieger et al., 2021).

Second Implication: New Salience of Extreme Voices

The second major implication for politics of the digital transformation of the public arena is that the Internet increases the salience of extreme voices. Looking at how extremist voices benefit from digital media, we see two central changes compared to a pre-Internet time. First, as outlined above, the Internet changes the opportunity structure for political outsiders and provides them with greater leverage in shaping public opinion. While political outsiders across the political spectrum – both moderate or extreme – can profit from this change, the digital success of the far-right in countries like the USA or Germany shows how extreme and authoritarian forces can use this new maneuver room to their advantage. Most importantly, they can mobilize their supporters (inward communication) and shape public opinion formation (outward communication) without having to rely on established the political and media institutions from which they were traditionally excluded in many contexts. In the past, extreme actors often would have experienced pressure to moderate their challenge towards established institutions in politics and media in order to get access to these institutions – for example, to get coverage in traditional media. However, being substantially less dependent on these institutions in the digital age, they now can remain extreme in their positions and challenge the established system without having to primarily rely on it.

Second, looking at digitally active citizens and their central role in the digital public arena, we see that the activities of commenting, sharing and liking are not uniformly distributed among all citizens, but are skewed towards users with extreme attitudes (Bail, 2021; Jungherr et al., 2020). The Internet functions as a feedback loop of extremism for these actors, who are most of the time embedded in more-or-less homogenous communities of users with similar extreme views, which normalizes their own extreme perspectives. However, at the same time, they are also regularly confronted with the other political side, quite often with the most extreme part of it. The substantial overestimation of the other side's extremism can lead to a backlash reaction and a strengthening of their own perspective, making their own extreme perspective seem more reasonable. Contrary to users with extreme attitudes, moderate users tend to opt out of engaging with politics, which skews the accumulated activities of commenting, sharing and liking towards the extremes. This kind of engagement feedback which the digitally active citizens provide to old and new media elites, political elites and civil society elites when participating in networked agenda setting and networked framing therefore tends to be a distorted one, where extreme voices are overrepresented and moderates underrepresented.

Third Implication: The Digital Amplification of Political Conflict

The third major implication of the digital transformation of the political public arena is the amplification of political conflict. Numerous scholars argue that digital media creates an environment that favors conflict-laden approaches, where the “in-group” is pitted against the “outgroup.” The basis for this argument is an view that political conflict is more often about the conflict of political identities than about the conflict of political positions on certain issues (Achen & Bartels, 2017). From this perspective, the essence of public opinion formation is not deliberation and rationalist argumentation, but emotions, post-hoc rationalization and, most importantly, identification with a particular political camp, whereby political identities tend to guide opinions on political issues, rather than the other way around. Political conflict therefore should not be understood as a rationalist exchange of arguments with the potential to convince the opponent. Instead, quite often, it is an attack of an outgroup by an ingroup the opponent identifies with, which will activate cognitive defense mechanisms such as anger. Brady et al. (2020) highlight that digital media create an environment where people’s political identities are hyper-salient and often under threat by political news or the confrontation with political outgroups. This, again, has implications for behavior: In this highly political environment, in the quest for social status within one’s own group (one of the most fundamental desires of human nature (Bail, 2021)) people are incentivized to express group-based moral emotions which aim at supporting their own group (elevation, awe) while attacking the outgroup (outrage, contempt).

What makes the presence and overrepresentation of extremism and conflict worrying is that the mechanisms of the intensified attention economy in the hybrid media system we described earlier seem to encourage such content. Brady et al. (2020) highlight that not only are people incentivized to express group-based moral emotions, but such moral emotions are also particularly strong in catching the attention of other users within the digital environment, lending those who express them an advantage in the fierce battle for attention within the public arena. While in pre-Internet times, extreme political outsiders might have managed to gain only limited media coverage, the intensified attention economy as well as economic and other pressures on traditional media might actually increase the chances for outsiders, as these factors have in some cases shifted traditional political coverage towards a more sensational bias which tends to favor political outsiders (Jungherr et al., 2020). Finally, there is a lively debate as to whether and to what extent platform design choices made in the interest of greater profit, such as a focus on increasing engagement, might artificially reinforce these dynamics (Zuboff, 2019).

Limiting Factors: The Internet Matters, but It is Not the Only Factor

While our argument so far seems to point towards a strong role of the Internet in shaping politics and feeding the rise of political outsiders, the salience of extremism and political conflict, there are three central limitations to its impact that need to be considered in this assessment.

The first is a reminder that the public arena is not just the Internet; rather, it is still dominated by traditional media outlets. As the Reuters Institute’s Digital News Report (Newman et al., 2021) demonstrates, together with other sources, the traditional media continue to dominate in many countries and are an important element of the public arena, affecting how people learn about and engage with politics and social issues. These media differ across countries. In some countries, many of them in Western and Northern Europe, strong and independent public service media continue to counterbalance some of the effects we have described above. In other places, most notably in the US, such institutions are less important while the media landscape is, at the same time, highly fragmented. In recent years, a network of conservative media has become increasingly separated from the rest of the media landscape (Benkler et al., 2018, 2020) and is highlighted as a major driver of the growing radicalization of the right – a general media phenomenon and not specific to digital media.

The second limitation is even more fundamental and crucial to note: Social and political clashes might be displayed and fought out in (digital) media, and digital media might indeed influence how these clashes are fought, but (digital) media is not the primary driver of these conflicts. The digital restructuring of the media landscape and the public and political arena affects the opportunity structure for political outsiders. It also shapes the structure of public opinion formation and opens the potential for extreme voices grow in influence and exacerbate political conflict. However, the mere existence of new opportunities does not automatically mean that they will be successfully realized. For this to happen, there must be a societal "demand" (Kaltwasser & Mudde, 2017) for extreme voices, political conflict and the politics offered by the political outsider. This demand only emerges in a dynamic with other societal factors and developments that are much larger and substantially more fundamental than the digital transformation itself. Without these factors, the success of political outsiders cannot be explained. Or as Jungherr et al. (2020) point out: We should not confuse the (digital) display of politics with its substance. The Internet is a venue for social and political conflicts, but not their cause.

Table 2: Supply and Demand for Outsider Politics. Self-created table. Developed based on Kaltwasser & Mudde (2017), reworked and extended based on Jungherr et al. (2020) and Schroeder (2018).

The third, and final, limitation relates to the fact that the transformation we describe here does not happen uniformly across countries, but is shaped by factors such as national media systems (Hallin & Mancini, 2004; Schroeder, 2018) and the general political context. Countries with intense commercial competition in the media sector seem to be more vulnerable to the increased competition-for-attention dynamics than systems with traditionally strong public broadcasting systems (Schroeder, 2018). At the same time, factors like media trust, but also general trust in the political system (which seem to be interlinked), are crucial factors in how digital media shapes power relations (Jungherr et al., 2020). This aspect of national contexts is especially important. A substantial amount of the research on the Internet’s impact on politics is carried out in the US, a country with a highly commercialized media system, a two-party system and a hyper-polarized political landscape, which therefore actually might be substantially more vulnerable to extremism and conflict amplification than other countries.

Interim Summary: An Era of Disruption and Turbulence

All these limitations and factors make it difficult to determine to what extent the digital transformation of the public arena re-shapes politics and, by extension, democracy. The extent to which the Internet does contribute to political polarization and related issues have sparked heated debates among the research community, with contradictory findings and no clear answers even after years of intensive research. While this does not necessarily contradict the changes and implications outlined earlier, it puts their (potential) impact into perspective. The Internet does change politics, but it is neither the only nor the most important variable contributing to political change.

The democratization of content production and distribution through the Internet has led to a shift of power within the public arena. New digital elites as well as digitally active citizens are playing an increasingly important role in setting the agenda in the public arena, while established actors in politics and media are losing their privileges in controlling and dominating the same. Together with the real-time characteristic of digital communication, the democratization of content contribution and distribution leads to rapid, and at times unpredictable and uncontrollable changes of the political agenda. This loss of control extends to and at the same time is rooted in a loss of control in the organization and mobilization of political action. New movements and actors can enter the public arena as political outsiders, introduce their issues and grievances and subsequently shape public discussion with unprecedented ease. These actors are not necessarily all extreme, but extreme actors certainly exploit this new maneuver space successfully. In all of this, the Internet can act as a key amplifier of political conflict and shape the nature of political discourse substantially. The Internet is not the cause of chaos, the emergence of extreme voices or conflict. Social grievances and real-world political conflicts are. But the Internet contributes to them. Politics in the digitally transformed public arena are characterized by rapidly shifting flows of actors, attention, activities and events as well as conflict and opposition towards the status quo. As Margetts et al. (2016) put it: “This is a turbulent politics, which is unstable, unpredictable, and often unsustainable.”

3. How to Manage the Digital Turmoil?

Digital disruption: Neither Good nor Bad, but a Force to be Reckoned With

We believe that the digital transformation of the public arena creates challenges and opportunities for our democratic systems, whereby we need to find a middle ground between containing the former and enabling the latter.

The most fundamental threat of this digital transformation is the potential for authoritarian abuse it entails. As already highlighted in Section Two, political outsiders profiting from the opportunities of the Internet, of course can be undemocratic, illiberal and/or authoritarian as well, and these actors could profit from an increase of the salience of extreme voices and the amplification of political conflict via digital media. Both factors could contribute to societal polarization (and there are good indications that they do so), which, at an extreme level, does open up additional opportunity spaces for these aforementioned undemocratic, illiberal and/or authoritarian actors.[4]

However, just as the Internet affords undemocratic, illiberal and/or authoritarian actors new possibilities, it also expands the opportunity space for the voices in our societies of those who are marginal, unjustly discriminated against or oppressed. They can more easily raise their voices, push their issues onto the agenda and shed light on their struggles. It has already been claimed in this paper that deeply rooted societal crises and grievances are the actual drivers of much of the political turmoil that displays itself on the Internet but are not rooted in it. Good examples of this are protests and movements around issues such as inequality, climate change, racism, homophobia and misogyny, all of which are urgent grievances that have profited (to some extent) from the Internet as an opportunity to push them into the public agenda.

What is essential to understand in this context is that conflict is not necessarily bad in itself (Echochamber.club, n. Y.). What for some might appear calm and peaceful, for others might feel like a debilitating silence. In fact, conflict might just be a sign of disagreement, and disagreement is a sign that our society is not a homogenous one but pluralistic and diverse. The many different parts of society might have different perspectives, and they might have good reasons for having them. What is needed is for our societies to learn to process these different perspectives in a way that makes it possible to air the underlying grievances and issues but does not lead to hyperpolarization and/or a political situation where the risk of authoritarian takeover increases. One challenge the digital transformation of the public arena might indeed lead to is more conflict, emotion and disagreement in a shorter period of time (speed is a real thing on the Internet, remember?) than our current systems are able to process.

Three Challenges We Need to Address to Manage the Digital Turbulence

Safeguarding democratic societies and the (digital) public arena

The first challenge we need to tackle is the authoritarian potential of digital media, which originates in the additional maneuver space for undemocratic, illiberal and/or authoritarian actors. In this context, it is important to remember that discussions about the possibilities and pitfalls of the re-shaped public arena have long been dominated by concepts (e.g. the “marketplace of ideas” and an expansive notion of freedom of speech) that have traditionally been popular in an Anglo-centric, and more specifically the US context. However, in recent years these concepts have been criticized for leaving the new digital public arena unprotected against the aforementioned enemies of democracy. As a reaction, there has been a substantial shift to much more restrictive governance approaches on most of the major platforms in recent years. At the same time, this shift has been accompanied by concerns about abuses of power and the potential shutdown of legitimate opposition by platforms and the state.

As the variety of challenges by authoritarian actors abusing democratic means to undermine democracy is probably as diverse as the democracies that have existed throughout history, Fertmann and Rau (2021) suggest looking beyond the US context to learn about how democracies might deal with this challenge in the digital space – for example to Germany.

The German constitution aims at fending off authoritarian attempts to abuse democratic means with a two-fold approach: First, it places the two central pillars of human dignity and fundamental rights (“liberal”) on the one hand and the idea that all power emanates from the people (“democratic”) on the other hand at the heart of German democracy. These pillars limit each other, the democratic pillar can never be used to undermine the pillar of human dignity. Second, and building on this idea of a partially limited democracy, the idea of a “fortified democracy” illustrates that democracies need to be able to defend themselves, building on two different angles to do so: On the one hand, this includes, if needed, the (partial) exclusion of democracy’s enemies from political participation processes. Such repressive measures, however, should always be only the last resort and their implementation needs to be embedded in a carefully designed system of checks and balances, including strong procedural rights for those affected such as the provision of adequate redress. On the other hand, and translating the constitutional concept into the pre-political sphere, its application in Germany also aims at building up democratic resilience and a democratic “immune system”. This angle includes education and the strengthening of democratic actors and institutions that operate with a view to inclusivity, diversity, respect and democratic norms – public service media, and an independent and free press, academia, civil society and citizens – as the first and most important layer of a fortified democracy..

What is important to highlight here is that such an approach only can be successful if we revisit our governance of digital media and further explore new means of democratic oversight over those digital intermediaries that act as central power brokers in the hybrid information system: The platforms, social networks and search engines that increasingly act as central gateways to information for many and therefore provide the infrastructure of the new digital public arena. Just as checks and balances exist for other institutions and actors in society to prevent power abuse and ensure democratic legitimation, they need to be applied here, too. Ultimately, all these points can be translated to how we think about safeguarding the digitized public arena. If these building blocks are solid, chances are that the public arena will be, too.

Build a conflictual, but non-polarizing (digital) public arena?

The second challenge that needs to be addressed is the question of how we can enable a process of politics within the digitally transformed public arena, which on the one hand allows for conflict and disagreement (necessary to ensure that the Internet still can serve as tool of empowerment for marginalized voices), while on the other hand does not facilitate hyperpolarization.

The scholars Daniel Kreiss and Shannon McGregor (2021) point out several important arguments in this context: They highlight that strongly articulated moral claims, strong collective identities and powerful emotions can be central building blocks for these marginalized voices to build communities and gain salience around and for their issues. Negative emotions of these groups towards “the other side” certainly seem rather justified, when this opponent camp also consists of far-right actors who have gained unprecedented influence. Based on these arguments, they argue that polarization seems more like an inevitable outgrowth of societal challenges and grievances the US is faced with than a crisis generated by the Internet.

While the US certainly is an extreme case in terms of societal grievances, a hyperpolarized landscape, and the degree of influence of authoritarian actors within mainstream politics (see above, re fending off authoritarian takeover), this discussion does show that there might be severely conflicting objectives in building something like an “ideal public arena.” Considering the example of emotion and conflict, we see these two elements can be simultaneously powerful (and necessary) tools for marginalized voices and contribute to polarization (which, as highlighted above, can itself become a maneuver space for authoritarian actors) and undermine cooperation and cooperative conflict solution (which may lead into political gridlock and an inability to find compromises and implement policies to tackle societal issues). What this example simply shows is that there is no unified answer to the question of what an ideal public arena could look like. Habermas’ idea of rational and calm deliberation in public debate is often invoked as a gold standard. In political theory, however, this question is heavily debated with thinkers like Chantal Mouffe strongly opposing Habermas, instead embracing conflict and emotionality as essential tools for marginalized voices (Mihai, 2014).

Navigating potentially conflicting objectives of a (digital) public arena such as freedom, pluralism, enabling of societal exchange, societal cohesion and a space for criticism and controlling of those in power (Heldt et al., 2021) will always be an extremely challenging task which needs to take into account all these different perspectives.

Translate digital turbulence into constructive politics

As we have argued, digital media are strong in enabling short-term political turbulence but they do not necessarily facilitate lasting and constructive political change. How should existing political structures be designed so that they turn input from a digitally transformed public arena into meaningful politics? We do believe that is one of the most fundamental challenges we are faced with due to the rise of the Internet, but here too, there are no easy solutions and answers. Yet, there are ways forward and we want to highlight three of them.

The first is that the issues and movements that express themselves through digital media are a force to be reckoned with and need to be listened to, both by the dominant political actors and the traditional gatekeepers to the public arena, even though it must be remembered that online political behavior does not reflect “the will of the masses, finally come to light” (Karpf, 2017, p. 174).[5] To some extent, digital media make this easier with new data and measurement techniques, allowing for the analysis of public sentiment and narratives. At the same time, digital media also facilitate the conversation between various actors in a society across time and locations. In future, we will need digital infrastructure and solutions that enable this listening and exchange at scale.

A second point is that our societies and institutions need to account for the fact that digital media and the internet have accelerated how we “do” politics and handle and debate matters of common concern. The structures and institutions we have built to govern ourselves need to become more aware and responsive to this new status quo, instead of hoping for it to revert back to the halcyon days of the pre-Internet age. We will need to learn how to establish mechanisms and systems which are able to cope with the speed of digital communication, which means they need to understand developments (see the first point) and react to them in (nearly) the same time as they unfold.

Third, and last, more creativity and experimenting is needed when it comes to formats that try to enable long-term constructive politics rather than short-term outrage on digital media (which, as we learned, does have its place, but there is a lot of the latter and less of the former)[6], not least because the search for such solutions continues. Digital “public assemblies,” for example, might be a viable avenue for channeling some of the input into existing political processes. Another example is Taiwan’s online polling system Pol.is, which integrates popular opinion into the legislative process. Also, political parties as a central cornerstone of many Western democracies need to explore new digital avenues of digital participation modes (Thuermer, 2021). Meanwhile, initiatives such as “My Country Talks,” which helps citizens to connect over the issues that divide them, can serve as inspiration for the construction of debating spaces that favor meaningful debate and exchange. Research like Bail (2021) highlights how digital platforms and discussion spaces can be designed to enable such constructive exchange. The question of how to include a meaningful representation of society within such participatory processes, rather than the usual large percentage of highly educated and active citizens will be a central challenge, as it is for all democratic processes, on- and offline.

4. Concluding Remarks

This essay has presented the argument that the digital transformation of the public arena can be powerful in enabling disruptive political turbulence, but often weak in transforming this turbulence into lasting and constructive political change. The democratization of content production and distribution, the real-time aspect of digital communication and an intensified attention economy (together with the general economic pressure on traditional media) can favor the rise of political outsiders, the increased salience of extreme voices and the amplification of political conflict. While digital media are not the sole cause of political and social conflicts in many Western democracies, they can play a role in exacerbating or expanding the same. At the same time, digital media provide authoritarian and anti-democratic forces, and are making new inroads into destabilize democratic systems. The emerging challenge is how we can utilize the democratic potential of the Internet and enable constructive and lasting political participation and digitally driven pushes for legitimate change, without feeding into (potential) death spirals of polarization and opening the door to those actors who seek to harness the affordances provided to them by our brave new digital world for their nefarious aims. While there will not be a silver bullet solution to this tension given the multifaceted and structural nature of many of the issues described in this essay, we can strengthen and safeguard the (digital) public arena, and by extension, democracy, by exploring the application of concepts like fortified democracy in the governing process of the (digital) public arena; , strengthening those institutions and actors that traditionally have acted as “braces” and have helped to keep societies together; by working on new ways of democratic oversight over those digital intermediaries that act as central power brokers in our modern societies; by finding a healthy balance between the different purposes and objectives a (digital) public arena should fulfill; by adapting our systems and institutions to the new speed of digital participation and by finding new ways and formats that channel political turbulence into meaningful and constructive political progress.

5. Further Reading

- Bail, C. (2021). Breaking the Social Media Prism: How to Make our Platforms Less Polarizing. Princeton University Press

- Freelon, D., McIlwain, C. D, & Clark, M. D. (2016). Beyond the Hashtags: #Ferguson, #Blacklivesmatter, and the Online Struggle for Offline Justice. Centre for Media and Social Impact.

- Jungherr, A., Rivero, G., & Gayo-Avello, D. (2020). Retooling Politics: How Digital Media Are Shaping Democracy. Cambridge University Press.

- Jungherr, A., & Schroeder, R. (2022). Digital Transformations of the Public Arena. Cambridge University Press.

- Margetts, H., John, P., Hale, S., & Yasseri, T. (2016). Political Turbulence: How Social Media Shape Collective Action. Princeton University Press

- Miller-Idriss, C. (2020). Hate in the Homeland: The New Global Far Right. Princeton University Press

- Schroeder, R. (2018). Social Theory After the Internet: Media, Technology, and Globalization. UCL Press.

- Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Teargas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Yale University Press

[1] It should be noted that this passage is largely a direct quote from Jungherr et. al. (2020) with a variety of smaller changes and adjustments. To increase the readability, we have refrained from highlighting every change we implemented.

[2] Following the work of Nancy Fraser.

[3] It should be noted that Kaiser & Rauchfleisch (2019), as well as Miller-Idriss (2020) and Rieger et al. (2021) write specifically about the far-right and the extreme right, and not political outsiders in general. However, we argue that the outlined insights actually can be generalized beyond the specific case of the far-right.

[4] The case of the US shows dramatically not only how a hyperpolarized political system (especially with high affective polarization) can suffer in its capacity to tackle societal issues due to political gridlock, but also, how eroded democratic norms and authoritarian actors can abuse this situation to gain power and influence (Levitsky & Ziblatt, 2018).

[5] As already indicated in Section 2, these participating digitally active citizens are not a representation of the population but are characterized by high (digital) news consumption, interest in politics, social status and on average more extreme political attitudes.

[6] As much as democracy is about political conflict, it is also about tackling and pacifying these conflicts and their underlying societal causes. And as much as disagreement, dispute and political fight are essential parts of this process, constructive exchange and debate, mutual recognition and understanding and building political compromises is, too.

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Tel Aviv and/or its partners.