Although mixed cities provide greater opportunities for Arab women, the unique character of these cities is largely to the detriment of the Arab population living in them. The impact of these conflicting trends on women in Israel’s mixed cities is presented through various data and analysis.

* This article is based on the chapter 'Mixed Cities' in the publication A plan to promote the integration of the Arab society in the labor market by Nasreen Haddad Haj-Yahya, Aiman Saif, Nitsa (Kaliner) Kasir and Ben Fargeon, which was published in collaboration with the Israel Democracy Institute and the Portland Foundation.

Introduction

The Arab population in Israel's mixed cities has a number of characteristics that set it apart from the rest of the Arab society in Israel. The proximity to the Jewish population has created a historical dynamic that is different from the rest of the Arab population in Israel, which lives in Arab localities. One may say that mixed cities are a microcosm of the relations between Arabs and Jews in Israel: They are characterized by socio-economic gaps, there is spatial segregation and the relations between the groups are conflictual. Alongside these, mixed cities also offer a unique space where the rigid boundaries of space and nationality are disrupted, and Jewish and Arab spaces mingle with each other (Monterescu, 2011). The place of Arab women in mixed cities and their integration into public spheres, such as the labor market and institutions of higher education, is also different from the patterns of integration of Arab women in non-mixed localities. The patriarchal supervision, which is present in Arab localities, is weaker in mixed cities. Therefore, it is not surprising that women's participation in the labor market and their integration in higher education outweigh their counterparts in Arab localities. In addition, mixed cities offer women a greater opportunity to participate in civic activities, in protest movements and political organizations. Thus, for example, in protests against violence and crime in the Arab society in Lod, the participation of women stands out (Samah Salaime, 2021).

Although mixed cities provide greater opportunities for Arab women, the unique character of these cities is largely to the detriment of the Arab population living in them. The liminal situation in which the Arab residents of the mixed cities find themselves often leads to disregard by both the state and the representative institutions of the Arab population in Israel. For example, in the last decade, several five-year plans have been set for the Arab society to advance its economic situation, but none has allocated resources to the Arab population of mixed localities. Their representation on the Supreme Monitoring Committee of the Arab Society and on the Committee of Heads of Arab Authorities [Municipal Localities] also began only in the early 2000s. In municipal politics, the Arab parties are usually not perceived as an integral part of the municipal coalition and cooperation with these parties is many times limited to specific interests. All this greatly reduces the agency capacity of the Arab population in mixed cities, and this fact is also reflected in relative difficulties in their integration into higher education and the labor market.

In this article, we will review the integration trends of the Arab population in mixed cities in the labor market and higher education in recent years. The comparison will focus on three main axes: women and men, Jews and Arabs and residents of the mixed cities and non-mixed cities. The findings show that on the one hand the socioeconomic level of the Arab population in mixed cities is higher compared to the Arabs living in Arab localities, and on the other hand the gaps in relation to the Jewish population in mixed cities are still strong and not sufficiently reduced. It also appears that in some of the indices there is a slower progression of the Arab population in mixed cities compared to the general Arab population, as stated, due to being a population that is in a liminal state and does not receive treatment in national or local politics.

Findings

The employment rates of the Arab population in mixed cities are considerably higher compared to the Arab population in Israel who lives in Arab localities, especially among women. The Arab population in mixed cities enjoys better access to the labor market in several respects. First, geographically the population of the mixed cities is closer to employment centers and to accessible public transportation compared to other Arab localities, most of which are in the geographical periphery of Israel. Second, the physical proximity to the Jewish population provides greater opportunity for the Arab population to learn the Hebrew language, which is the dominant language in the Israeli labor market. Third, at least in some of the mixed cities, the Arab education system is better than the Arab education system in Arab localities and thus provides a greater opportunity for its students to be eligible for quality matriculation leading to higher education and finally also to easier labor market integration. Moreover, Arab society in mixed cities is less conservative and the patriarchal supervision much less rigid, which explains the relatively high proportion of Arab women integrated into the labor market.

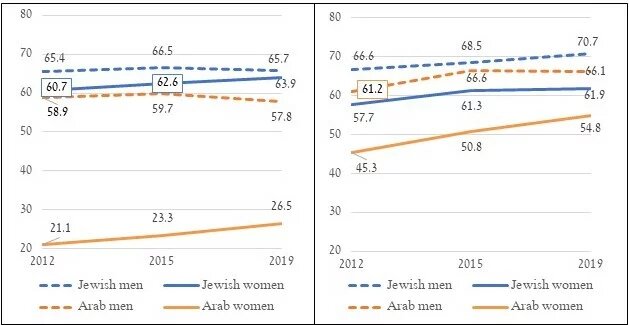

As of 2019, the employment rate of Arab women from mixed cities was 54.8%, significantly higher than the employment rate of Arab women from non-mixed cities (26.5%) but lower than the national employment rate of women in Israel - 57.2%. Among Arab men the gap is smaller but still significant - the employment rate of Arab men from mixed cities is 66.1% compared to 57.8% among Arab men from non-mixed cities. Despite the high employment rates of Arab women from mixed cities, among Arab women from non-mixed cities there was a greater increase in 2012-2019 and thus the gaps between the two groups narrowed. In contrast, among Arab men, who are not from mixed cities, there was a 2% decrease in employment rates in 2012-2019 and thus the gap between them and men from mixed cities, whose employment rate actually increased, only widened in these years.

It is possible that the reason for the lower increase of employment rates of Arab women from mixed cities lies in the fact that the programs for integration of the Arab population in general, and the Arab women population in particular, focused less on the mixed cities and a gap was created in this matter between the mixed cities and the areas in which funds were invested and programs were implemented. A prominent example for this is the exclusion of Arabs from mixed cities in Program 922, the Israeli government's flagship program for economic development of the Arab society that operated during the years 2016-2020 with a budget of about NIS 10 billion. As part of the program, many resources have been invested to integrate the population of Arab localities, especially the female population, into the labor market and employment-supporting infrastructures (such as transportation and nursery schools for infants and toddlers). Although the Arab population in the mixed cities is about 10% of the total Arab population, it has been completely excluded from the program.

It is worth noting that the gap in the employment rate between the Arab and Jewish populations in mixed cities also narrowed in 2012-2019. If in 2012 the gap in employment rates between Arab women and Jewish women from mixed cities was 27%, by 2019 it was reduced to 13%. Among men, the gap narrowed from 9% to 7% during those years.

Chart 1: Employment rates among people aged 15+ by gender and population group, 2012-2019 (%)

Non-mixed cities Mixed Cities

Source: The authors' processing to the data of the Central Bureau of Statistics

Difference between different mixed cities: The relatively high employment rates of Arab women and men in the mixed cities obscures the marked differences that exist between different mixed cities. In some of the mixed cities, employment rates are particularly high, and the Arab population is sometimes even better off than the Jewish population. But in some of the mixed cities the situation is very poor and the population in these cities participates in the labor market at low rates similar to the rest of the Arab society, despite high accessibility to the labor market.

Prominently for the worse among Arab women is Lod, where only 41% of Arab women are employed. Moreover, in 2015, the employment rate of Arab women in Lod was 39% and thus, in contrast to the relatively high increase of employment rates of Arab women who are not from mixed cities, the employment rate of Arab women in the city by 2019 increased only slightly. On the other hand, the employment rates of Arab women in Jaffa (66.4%) are particularly high (even higher than the Arab men in Jaffa), and in Haifa they are also relatively high (however, in Haifa there was a decrease in the employment rates of Arab women in 2015-2019, from 56% to 54.8%).

Among Arab men, employment rates in Ramla (52.5%) and Lod (62.1%) stand out for the worse. In these two cities, there was a sharp decline in the employment rate of Arab men between 2015 and 2019. In Lod, the employment rate of Arab men fell from 71.4% to 62.1% and in Ramla from 57.2% to 52.5%. Similar to Jaffa, as of 2019 the employment rate of women is higher than that of men. In both Jaffa and Acre, the employment rates of Arab men decreased during these years, and only in Haifa was there an increase.

Chart 2: Employment rates among Arab women and men aged 15+ in mixed cities according to cities, 2019 (%)

[Arab Men] [ Arab women]

Source: The authors' processing to the data of the Central Bureau of Statistics

Figure 3 indicates an increase in the rate of Arab women with an academic degree in the mixed cities, from 16.3% in 2012 to 22.1% in 2017 (an increase of 36%). This increase is greater than the increase among the other populations in the mixed cities (Arab men, Jewish women, and Jewish men), which stands at about 10% in each of them. Between 2012 and 2017, the gap between Arab academic women and Jewish academic women and men in mixed cities narrowed (from a gap of 19.7 to 16.5 percentage points compared to Jewish academic women, and from a gap of 15.4 to 12 percentage points compared to Jewish academic men). Due to the moderate increase rate in the academic Arab men, there is still a large gap between them and the Jewish population. The fact that less than one-fifth of Arab men in mixed cities have an academic degree impairs their ability to advance in wages and rank in the labor market. As we will see below, the level of education has a strong impact on the ability to integrate into the labor market and the level of the individual's salary. These, of course, also have a direct impact on a family's risk of living in poverty. According to data from the National Insurance Institute for 2018, the poverty rate of families headed by those with low education (up to 8 years of schooling) is 46% compared to 20% among families headed by high school graduates (9 to 12 years of schooling) and only 13% among families headed by a person with higher education (13 years of schooling or more) (National Insurance Institute, 2019).

Chart 3: Percentage of academics aged 18+ in the mixed cities in 2012 and 2017 by population group and gender (%)

Source: The authors' processing to the data of the Central Bureau of Statistics

Figure 4 presents the main industries in which the Arab and Jewish populations work. The chart shows that almost a quarter of the Arab women living in mixed cities (22.8%) worked in the education industry in 2017, a much higher rate than the rest of the population groups in mixed cities but lower than the national rate among Arab women (30.3%). Another major industry in which these women worked was health services (18.9%). This industry also has a greater representation of women in general, and Arab women in particular, compared to men (17.9% of Jewish women, 9.7% of Arab men and 4.6% of Jewish men). The trade and repair industry is the third largest industry in which Arab women worked (16%). Between 2012 and 2017, there was almost no change in the distribution of Arab women employees in each of the three industries. Among Arab men in mixed cities, about one-fifth were employed in the trade and repair industry, more than twice compared to Jewish men. In addition, both among Arab men and among Arab women from mixed cities there is a relatively high proportion of employed in professional, scientific and technical services (7.2% and 6.6%, respectively) compared to the national average (3.2% among Arab women and 3.6% among Arab men). The data show that among Arab men from mixed cities there is a relatively balanced distribution between different industries. This contrasts with the concentration of Arab men not from mixed cities in construction and manufacturing industries, where there has been a significant decline in the employment rate in recent years. This balanced distribution may have protected Arab men from mixed cities from a decline in the employment rate during the five years 2012-2017.

Chart 4: Key industries among employed persons from mixed cities aged 18+ by population group and gender, 2017 (%)

* This chart contains only the main industries. Since this is a relatively small population, and they are scattered in a large number of industries, in some industries there were too few observations and therefore it is impossible to present them.

Source: The authors' processing to the data of the Central Bureau of Statistics

The data in Chart 5 show that between 2012 and 2017 there was almost no change in the rate of Arab women in mixed cities employed part-time (from 35% in 2012 to 33.3% in 2017), as well as in the rest of the populations (Arab men, Jewish women and Jewish men). The stagnation in the proportion of Arab women from mixed cities who are employed part-time stands in contrast to the nationwide trend. Among Arab women from the rest of the country, there was a decrease from 32% in 2012 to 24% in 2017, and in fact today the proportion of Arab women employed full-time is higher than the corresponding rate among Jewish women. The reason for the stagnation probably lies in the fact that unlike Arab women, who are not from mixed cities, a lower proportion of Arab women from mixed cities are interested in working full time. In evidence, although there was a very moderate decline in the proportion of part-time employees, the percentage of Arab women who indicated that they were involuntarily employed part-time decreased between 2012 and 2017 by 29% (from 26.8% to 20.8%) (Chart 6). These data are somewhat surprising, since it could be expected that in mixed cities, where there is increased interaction between the Arab population and the Jewish population, the patterns of participation in the labor market would be more similar.

|

Chart 5: Proportion of part-time employees from mixed cities by population group and gender (%) |

Chart 6: Proportion of people employed part-time involuntarily from mixed cities by population group and gender (%) * |

Source: The authors' processing to the data of the Central Bureau of Statistics

* Data on Arab men are not shown due to a small number of observations.

Wage gaps: In the years 2012-2017, the average monthly wage of Arab women in mixed cities increased by 14.1% (from NIS 6,399 to NIS 7,302). In contrast, the average wage of Arab men in mixed cities did not change much: between 2012 and 2015, their wages decreased, but by 2017 it had returned to its previous level (Figure 7). During these years, the wages of Jewish men and women in mixed cities increased by 17%, and thus the wage gap between the two populations only deepened. In 2012, the monthly wage gap between Jewish and Arab women was 35.8%, and from then until 2017 it rose to 39.3%. The gap in the monthly wage between Arab women and Arab men has indeed narrowed, however the gap between Arab men and Jewish men has risen sharply, from 23.9% to 41.2%. At the national level, the wage gaps between Arabs and Jews also widened, and although in 2012 the gaps in mixed cities were lower than the national level, in 2017 they were already similar.

Chart 7: Real Monthly Wages * Average (Gross) for Employed Persons from Mixed Cities by Population Group and Gender (NIS)

* The wage is a real wage whose base period is 2018 = 100.0.

Source: The authors' processing to the data of the Central Bureau of Statistics

The level of education has a great impact on both the ability to integrate into the labor market and the earning capacity. The employment rate of Arab women from mixed cities whose level of education is up to a matriculation certificate (inclusive) stands at only 52%, compared to a rate of 82% among academics. Among Arab men, the impact is less powerful, but it is also noticeable - an employment rate of 72% for those whose level of education is up to a matriculation certificate (inclusive) and 86% for academics.

Not only are the employment rates of academics from Arab society higher, but their salaries are also considerably higher. In 2017, the monthly salary of Arab women from mixed cities with academic education was 2.27 times higher than the monthly salary of Arab women from mixed cities without academic education (NIS 12,130 compared to NIS 5,330, respectively). Arab academic men in the mixed cities also earned immeasurably higher wages than their non-academic counterparts. In 2017, the average salary of an academic Arab man in a mixed city was NIS 23,485, compared to only NIS 8,348 (2.8 times) for a non-academic Arab man. This wage is also much higher than the wages of academic Arab women from mixed cities. It is interesting to realize that in the mixed cities, the wage gap between academic Arab men and academic Jewish men is negligible and stands at only 4.1%. Compared with a gap of 37.4% between non-academic Arab and Jewish men from mixed cities. In this regard, it is worth noting that about 80% of the Arab men employed from mixed cities are not academics, and 61% have only a matriculation certificate. This means that most Arab men do not enjoy a high salary. Furthermore, the wage presented is the average wage for all the mixed cities and does not take into account the differences between them. For example, it is known that the average wage in Lod, Ramla and Acre, for Arab women and men, is very low and only slightly higher than the minimum wage (Haj Yahya, 2019).

Government investment for involving the Arab population in mixed cities in general, and Arab women in mixed cities in particular, in the labor market will serve not only the Arab population but the mixed cities in general. In cities like Lod, Ramla and Acre, the inclusion of Arab women in rewarding employment will create a wheel of positive impact on the well-being of the population and in its power to also reduce crime significantly in these cities, as the entire household will enjoy higher incomes.

Summary

For many years the Arab population in mixed cities "fell through the cracks." Its representation in the institutions of internal Arab politics has been lacking, it has been excluded from government programs for the Arab society in Israel and as a minority in every city its ability to influence municipal politics has been limited. In recent years, mainly by the push of elements from civil society, and in the last year due to the wave of violence during May 2021, the mixed cities are getting a wider stage in the political, public and media discourse. On the part of politicians, decision-makers and policymakers, the understanding permeates that the mixed cities require an investment that takes into account their unique characteristics, and more importantly, the unique characteristics of each city separately.

The data presented in the article leave no room for doubt - the employment and education situation of the Arab population in mixed cities is immeasurably poor compared to the Jewish population living in those cities. The rate of academics, the rates of employment, the level of wages and the industries of employment indicate clear differences between the two populations. In recent years there has been indeed some reduction in the gaps in some of the indices, but they are still deep. Although the socioeconomic status of the Arab population in mixed cities is better than that of the entire Arab population, the immediate group of comparison is the Jewish population living in the same city. When the Arab population in mixed cities sees that its neighborhoods are neglected, the level of education is low and the housing problem becomes an unbearable burden while "Jewish" neighborhoods enjoy preferential treatment in municipal and government services, planning and construction issues, much anger and frustration accumulate. Many among the younger generation in mixed cities feel they have no horizon and aspirations in the fields of education and employment. The employment situation and the height of the flames in the May 2021 events in each city cannot in fact be directly linked, since the causes of the outbreak are many and complex, however, the lack of integration of the Arab population, especially young Arab men, attests to deep frustration and limited chances of living well in each city. For example, the employment situation of Arab men in Lod, Acre and Jaffa deteriorated following the covid-19 crisis and these cities were the focus of violent outbursts. In Haifa, Nof Hagalil and Maalot-Tarshiha, the employment situation is better and in these cities were relatively calm.

1 Daniel Monterescu, 2011. Identity without community, community seeking identity: Spatial politics in Jaffa. Megamot [Trends] (3) 4, 484-517.

2Samah Salaima, The activists in Lod are determined: Not even the arrest of the children will not stop the protest, local conversation, 14.09.2021.

3The Social Security Institute, The Dimensions of Poverty and Social Disparities 2018, December 2019.

4 Nasreen Haddad Haj Yahya, Arab Women in Mixed Cities in Israel, Van Leer Institute Articles Blog, January 1, 2019