Who is the Israeli man? What are his perceptions and views regarding gender issues? In what way, in his opinion, should household and childcare chores be divided between couples? To answer these questions, we conducted a study aimed at characterizing masculinities in Israel. This was done by means of an online survey among 506 men, 405 Jews and 101 Arabs, constituting a representative sample of Israeli men aged 18 and older. [1]

Perceptions of Masculinity

Many men (and women) in Israel were educated and brought up within a gender perspective that is based on traditional conceptions of masculinity. A key component of these perceptions is that men, more than women, should avoid showing weakness and pain. Indeed – a significant percentage of the men who took part in our research agree with this view (75%). No differences regarding this issue were found between Jews and Arabs, between different age groups, or between various educational or income levels. A certain gap can be found within the Jewish population, when segmented according to the degree of religiosity. The religious (83-84%) and the orthodox participants (87%) showed more agreement with this notion than the secular Jewish participants (65%).

Alongside the need to avoid expressing emotion, mainly weakness and pain, a central component in the sociology of gendering emotions is related to military service. The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) as a state organization, and especially combat roles in the army, constitute a key agent of socialization in the formation of (Jewish) masculine identity in Israel, an identity centered on wielding power, aggressiveness, and violence, an identity characterized by feelings of superiority toward women and, to a large extent, by the exclusion of women. The vast majority of men in Israel, and especially Jewish men, believe that serving in a combat unit turns boys into men (Jews – 72%, Arabs – 54%), meaning that even in current-day Israel, one of the main paths to acquiring masculine, traditional-hegemonic identity, passes through military combat roles, roles which are awarded with substantial social and symbolic capital over the years.

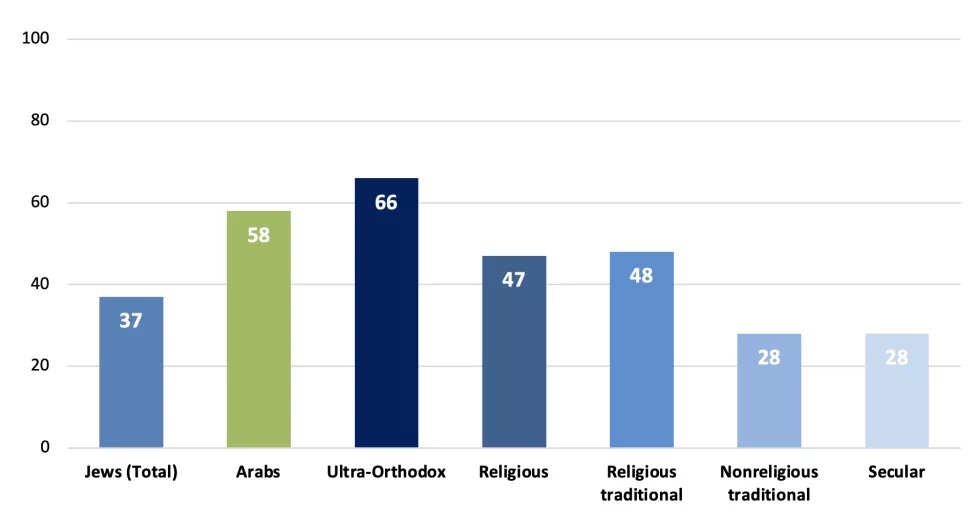

However, in recent years, one can identify cracks in the perceptions of Israeli men regarding the characteristics of masculinity in current Israeli society. One such expression can be found in the fact that a small majority of men does not agree that men, more than women, think logically and act out of rational motives. This means that over half the men oppose identifying cold-minded rational thinking with men alone. Most supporters of the traditional perceptions of masculinity are found within the Arab society (58%), compared to a minority within the Jewish public (37%). In this case too, among the Jewish participants, a connection was found between one’s position on the issue and one’s religious identity: While approximately two-thirds of ultra-Orthodox men agree that men think logically and act in a calmer manner than women, and almost one-half of religious men agreed with this statement, approximately one-quarter of non-religious people agree with the statement. We can thus surmise that the level of identification with a traditional perception of masculinity regarding logical thinking and rational motivation to act depends largely on one’s position on the religiosity scale.

Men, more than women, think logically and act out of rational motives (% agree)

Another issue on which we can see a change in men’s position – albeit a partial one – is in regard to the situation of women in society. Less than half the men (46%) agree that the mass-media focuses too much on issues of discrimination against women, while in fact their situation is better than portrayed. And yet, this is another issue where significant gaps occur between the various groups – from the secular to the ultra-Orthodox – within the Jewish population: while the majority of ultra-Orthodox and religious men agree that mass-media focuses too much on issues of discrimination against women, although their situation is better than portrayed (ultra-Orthodox 63%; religious 55%; religious traditional 57%), in fact only a minority of non-religious Jews agrees with this view (secular 35%; nonreligious traditional 42%).

The Division of Roles in the Labor Market and in the Domestic Sphere

One of the main issues regarding the gender perceptions of both men and women is related to women’s employment. From the 1960s onwards, the world saw a significant increase in women’s employment in paid jobs outside their homes, as well as an increase in the number of hours they worked. We can also see a change, albeit a slow one, in women’s areas of employment and in the proportion of women filling management roles. But despite these changes, which are evident for several decades, the gaps between men and women in the labor market are still significant. These are gaps in salaries, in the scope of the jobs, and in the proportion of those reaching senior managerial roles.

One of the barriers obstructing women’s progress in the labor market is due to the gender perceptions held by those wielding power and hegemony in this arena – that is, men. The traditional view, that women’s role, first and foremost, is to take care of the home and family, still receives significant support from men: 34.5% of men in our study agreed that family life is adversely affected when the mother works full-time. Most supporters of this position can be found among Arab men (53%), while – in accordance with this view, according to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), only 40% of Arab women are currently employed in paid jobs. The segmentation of Jewish men’s views according to their degree of religiosity, shows, yet again, considerable differences between religious groups: Even though according to the CBS, 75% of ultra-Orthodox women are employed in paid jobs, almost half of ultra-Orthodox men agree that family life is harmed when the mother works full-time (46%). On the other hand, only 22% of secular men agree with this statement, as opposed to 76% who disagree.

Family life is adversely affected when the mother works full-time (%, agree)

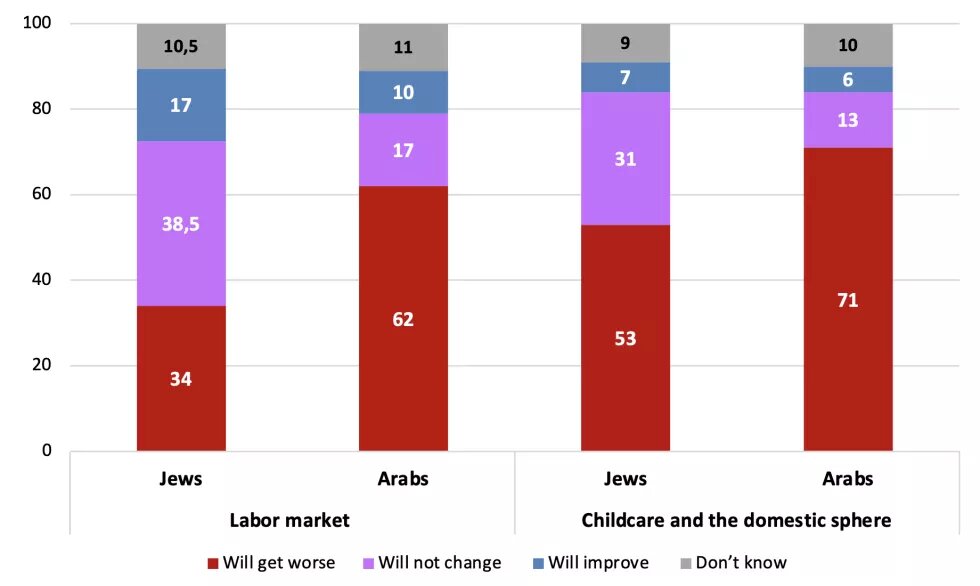

In Israel, as mentioned above, the proportion of men in the labor market is greater than that of women. In the domestic sphere, the situation is the opposite, and even less balanced than in the labor market, since in regard to taking care of the children and performing various home chores, the percentage of women is much higher than that of men. We asked – what would happen to these two arenas – the labor market and the domestic sphere, if the situation was reversed – if the percentage of women in the labor market was larger, and if the percentage of men in the domestic sphere was larger? The men’s responses reveal how strong they see the connection between women and the home arena: most men who took part in the study (56%), stated that childcare would be adversely affected if women’s share in the domestic arena were decreased, and men’s share was increased. A lower percentage of men who took part in the study (39%) believe that the labor market would be harmed under a female – and not a male – majority. Approximately one-third of the men (35%) believe it would not change, and 16% believe the labor market would improve.

The traditional perception regarding the role of women and men in society is far more dominant among Arab men than among Jewish men: in both groups there is a majority who believes childcare would be harmed if the percentage of women in the domestic arena was to decrease, and the percentage of men was to increase, but Arab men agree with this view more than Jewish men (71% in comparison to 53%). A similar depiction, with an even larger gap, was found when examining men’s perceptions as to what would happen to the labor market under a female majority. More than 60% of Arab men thought the labor market would be harmed, compared to approximately one-third of Jewish men who believed that this would be the case.

What would happen to the domestic sphere if the share of men was greater than that of women, and what would happen to the labor market if the share of women was greater than that of men? (%, Jews and Arabs)

Substantial gaps regarding this issue can be found within the Jewish public, segmented by position on the religiosity (secular-Orthodox) scale. A large majority of ultra-Orthodox men believe that childcare and other domestic chores would be harmed if these were to be done by men more than by women. They also believe that the labor market would be harmed if the percentage of women in this arena was larger than that of the men. A majority for such beliefs regarding the domestic sphere and childcare being harmed can also be found among both religious Jews (two-thirds) and religious traditional Jews (55%) as opposed to a minority (though a significant minority) of non-religious Jews who hold these positions (45% of the secular and the nonreligious traditional Jews). Secular Jews are also those who least agree with the view that the labor market would be harmed under a female majority (less than one quarter hold this view).

The domestic sphere will be harmed if most of the caregiving is done by men, and the labor market will be harmed if most of the employees are women (%, Jews, by religiosity).

These attitudes, regarding the link that many of the men make in relation to the two arenas – the domestic sphere and the labor market – are also evident from their answers regarding how the different roles should be divided: earning a livelihood, taking care of young children, performing household chores, and educating children. 38.5% of the men believe that earning a livelihood for the family should be solely, or mainly, the father’s role, while only 5% of the men believe that household chores, such as cleaning and laundry, should be performed mainly by men. A similar percentage believes that taking care of young children should be performed mainly by the fathers.

And what about the role of women? Only 1.5% of the men believe that the family’s livelihood should depend solely, or mainly, on the mothers, compared to a much larger percentage which believes that childcare and household chores should be carried out solely, or mainly, by the mothers: childcare – 38%; and household chores – 28%. These numbers are in line with the actual division of roles in the domestic sphere between women and men: in heterosexual families in Israel, almost two-thirds of household chores and childcare are performed by women, and only about one-third by men.

The domestic chore for which the highest proportion of men (over 80%) believe should be shared equally by the couple, is that of the children’s education. The proportion of men who believe that this should be done solely, or mainly, by the fathers, equals the proportion of men who believe this should be done solely, or mainly, by the mothers (9%).

The division of different tasks (%, the entire sample)

Regarding these questions too, Arab men express more traditional and conservative positions than Jewish men: two-thirds of Arab men believe the family’s livelihood should be provided solely, or mainly, by the fathers, and only 28% believe that this responsibility should be shared equally by the couple. Among Jewish men the picture is reversed: two-thirds stated that family livelihood should be shared equally, and 33% stated that the fathers should be solely, or mainly, responsible.

Regarding childcare and household chores, responses of Jewish men are a mirror image of those of Arab respondents: Nearly one-half (48%) of Arab men stated that childcare should be performed solely, or mainly, by the mothers, and less than one-third (30%) stated that childcare should be divided equally between the parents. Among the Jewish population, 36% stated that childcare should be solely, or mainly, the mother’s responsibility, and the majority (62%) stated that childcare should be equally divided between the parents. Regarding household chores, the vast majority of Jews stated that they should be equally divided by the couple (73%), while in the Arab sector, only 37% chose this position, and a greater percentage (41%) believe that it is only, or mainly, the mothers who should perform the various household chores.

Men and Feminism

The next issue examined in this study was that of men’s perceptions regarding the feminist movement. The men who took part in this study are divided in their views regarding the impact of feminism on men in Israel – does it help or harm them? And what is feminism’s effect on gender equality? 40% of the men who took part in this research believe that feminism contributes to gender equality in Israel, while an almost similar percentage (42%) believe that it harms gender equality. It was also found that about one-third (32%) of men believe that feminism benefits men in Israel, as opposed to almost one-half (48%) who believe that feminism harms men.

When segmenting the Jewish public according to their position on the religiosity scale, it is evident that on this issue, secular Jews hold the most positive views toward the feminist movement: half the secular men believe that feminism contributes to gender equality. In regard to its influence on men, answers are divided (38% – contributes; 40% – harms). On the other hand, in the ultra-Orthodox and religious public, the vast majority believes that feminism harms gender equality (53%–59%), and an even higher rate (61%–75%) believe that it harms men in Israel.

Does feminism help or harm gender equality and does it help or harm men in Israel? (%, Jews)

Masculinity and COVID-19

In the State of Israel, many of those filling key positions in the public sphere are men – be it senior roles in the labor market in general, or in decision-making centers in the political system in particular; in these spaces, women still comprise a minority. We asked the following: “In Israel, the COVID-19 crisis is managed mostly by men (the Prime Minister, Minister of Finance, Minister of Health, Minister of Defense, Director-General of the Health Ministry, the COVID-19 Project Manager, and so on). "How would the COVID-19 crisis have been managed if the main roles had been filled by women?”

Among the more optimistic outcomes of this study are the men’s attitudes on the aforementioned question. It was found that men’s positions are divided, with a tendency to prefer female management: almost one-third of men stated that women would have managed the current crisis better than it is currently being managed by men. A similar proportion stated that the crisis would have been managed in a similar manner, and only 16% believe that had women managed the COVID-19 crisis it would have been managed worse.

How would the COVID-19 crisis have been managed if women had played key roles? (% answers)

Differences of opinion between Jews and Arabs were found on this issue as well: 32% of Jewish men stated that the COVID-19 crisis would have been better managed by women, and only 12% stated that it would have been managed in a worse manner. Among Arab men, 34% stated that women would have managed it worse than men, and 24% believe that women would have managed the crisis better.

Among the Jewish public, most support for female management was found among secular men (42% – the crisis would have been better managed; 5% – the crisis would have been managed in a worse manner), and in the religious traditional sector (32% – better managed; 11% – managed in a worse manner). The greatest opposition to female management was found among ultra-Orthodox men (13% – better managed; 29% – managed in a worse manner) and among the religious sector (16% – better managed; 18% – managed in a worse manner).

Summary

There are a number of conclusions arising from this study. First, it is highly important to break down, segment and analyze in-depth the term “masculinity in Israel”, which tends to see men as one homogenous block. Israeli men hold diverse opinions regarding Israeli masculinity, the division of roles in the domestic sphere and the labor market, and in their views regarding the feminist movement. Even today, in 2021, a significant proportion of men still hold traditional-hegemonic views as to the division of roles of the sexes in general, and to men’s roles in particular, views that differentiate widely between the “proper” roles for each of the genders in each of the arenas. On the other hand, the current study reveals that a growing proportion of men who hold liberal and more egalitarian perceptions regarding masculinity, who oppose the traditional-hegemonic conceptions of masculinity, and who oppose the dichotomous division of roles between the sexes. Even so, we must mention that different studies conducted during the last decade in Israel and around the world, found that while changes in the positions and views and attitudes expressed by men have indeed occurred (as the current study shows), actual changes in men’s involvement in the domestic sphere, and changes in equality levels in the labor market, are fewer and happen much more slowly.

Second, when describing perceptions and attitudes regarding gender issues in general, and perceptions of masculinity in particular, it is important to look deeply into the different social groups that make up Israeli society. This gaze highlights the gaps in the positions of the different social groups. Generally, Jewish men express less identification with traditional masculine perceptions compared to Arab men, Jewish men hold significantly more egalitarian positions regarding the roles of men and women in the labor market and at home, compared to Arab men. Within the Jewish public, as was evident throughout this study, differences were found in almost all matters discussed, between different groups of religious classification – a strong connection was found between one’s position on the scale of religiosity and liberal or conservative views on gender issues: secular men voiced the most liberal and egalitarian positions, while religious and ultra-Orthodox men expressed the most conservative views. Analyzing the data shows that when examining gender perceptions and the ideology of masculinity, one’s position on the scale of religiosity is the most significant factor in the analysis of such views within the Jewish public – more than levels of education, age, or income.

In conclusion, and looking to the future, one can also draw optimism from this study. A growing number of men in Israel today oppose traditional perceptions of masculinity, believe in an equal division of roles between couples, and oppose the linkage between home and motherhood, and the labor market and fatherhood. I claim that to bring about social change, which leads to a situation where the change in attitudes is manifested in practice, such perceptions must be leveraged, promoted, and made visible in the public sphere, and a structured work plan should be formed to enable and encourage men to act daily in accordance with their positions and perceptions, without them having to pay a “social fine” for implementing these perceptions in practice. It is evident that a growing proportion of Israeli men are interested in seeing such a change, wishing to live in a more egalitarian world than that of their parents. To do so, joint collaboration between women-led feminist movements, and men who wish to promote social change in these matters, may lead to the long-awaited for social change, and lead us toward a more gender-equal society.

[1] The research presented in this paper is based on data obtained from a survey on masculinity in Israel conducted by Dr. Or Anabi for the Heinrich Böll Foundation. In this survey, conducted both online and by telephone (to complete the sampling of those groups not adequately represented on the internet), from January 28th-31st 2021, 506 men were interviewed – 405 in Hebrew and 101 in Arabic. These men constitute a representative national sample of the entire male adult population of Israel aged 18 and older. The maximum margin of error for the entire sample was ±4.44%, with a confidence level of 95%. The field work was conducted by the Smith Consulting Institute.