The term “tech diplomacy” has gained currency over the last five years. The following text aims to unpack it and highlight specific examples of tech diplomacy practices.

The term “tech diplomacy” has gained currency over the last five years. It refers broadly to recent shifts in diplomatic practice that have formed as a response to the increasing impact of digital technologies on global politics and international relations alongside the growing dominance of a handful of technology companies. Examples of emerging diplomatic practices include the appointment of tech ambassadors and other envoys as well as a variety of forms of diplomatic representation in Silicon Valley. Some countries have already published dedicated digital foreign policy strategies. The following text aims to unpack the term “tech diplomacy” and highlight specific examples of tech diplomacy practices.

THE FIRST ENVOYS: TECH DIPLOMACY ENTERS THE CONVERSATION

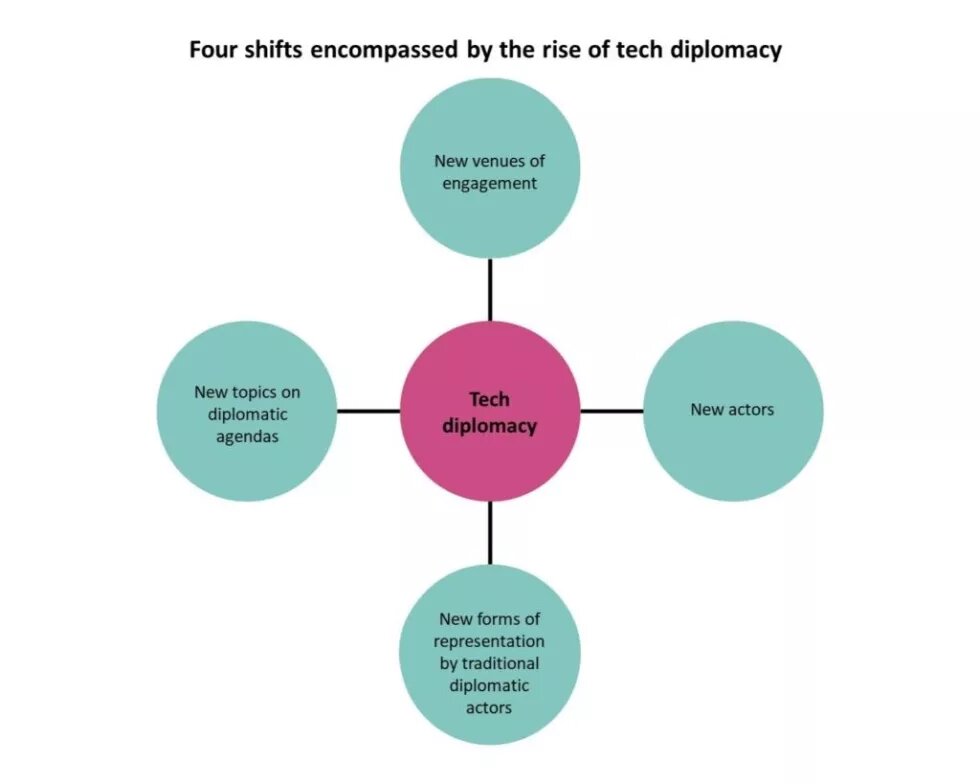

A traditional perspective within diplomatic studies describes diplomacy as the management of international relations by selected representatives of the state, usually professional diplomats. Tech diplomacy recognizes that topics related to digital technology have become important to managing international relations and that this also means that a new set of actors, mainly big tech companies, need to be taken into consideration and engaged accordingly as part of diplomatic practice. In this sense, tech diplomacy encompasses four shifts: New forms of representation by “traditional” diplomatic actors, new topics on diplomatic agendas, new actors, and new venues of engagement.

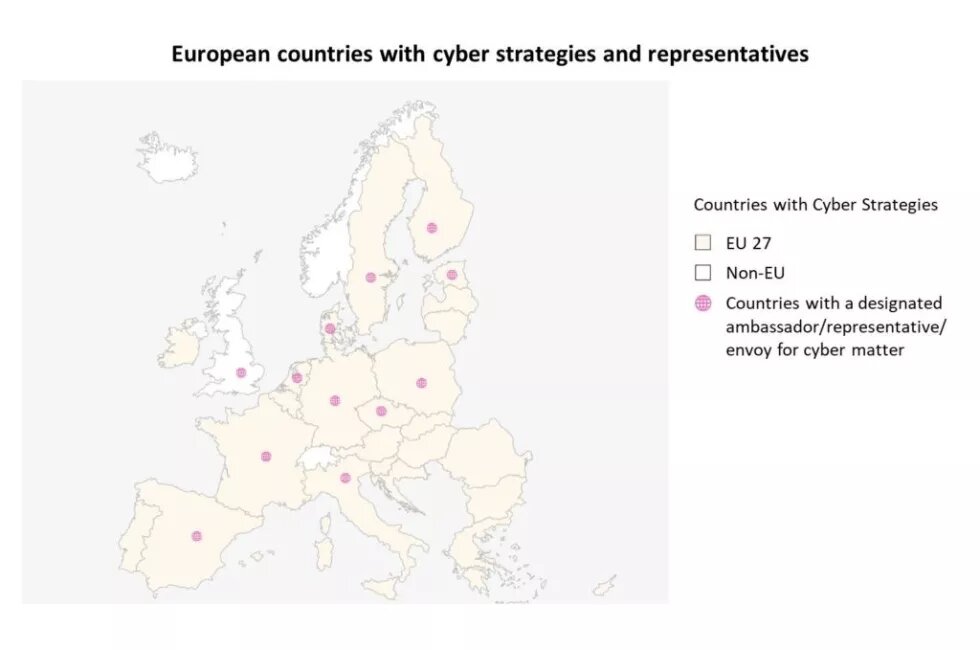

The first prominent appearance of the term “tech diplomacy” was in conjunction with the appointment of the Danish Tech Ambassador, Casper Klynge, in 2017. Australia also appointed its first tech ambassador in 2017, choosing the title Ambassador for Cyber Affairs and Critical Technology. Some earlier practices include the US State Department’s Coordinator for Cyber Issues and the tech-policy-related work of the UK Consul General to San Francisco. Since these early initiatives, a number of countries have followed suit and appointed tech ambassadors and other tech diplomats. A brief by the European Parliamentary Research Service from 2020 identified 12 such positions in Europe, while a study by the Tony Blair Institute from 2022 identified 19 appointments of tech diplomats world-wide.

Countries that have started to engage in tech diplomacy have made use of a plethora of practices that go beyond the appointment of tech ambassadors. Focusing on diplomatic representation in Silicon Valley, a DiploFoundation paper identified various “models of interaction and representation,” suggesting that the appointment of tech ambassadors is but one form of conducting tech diplomacy. Further models of interaction and representation include consulate generals using traditional diplomatic approaches, setting up innovation and investment centers, and appointing honorary consuls.

Beyond representation focused specifically on Silicon Valley and other tech centers, some countries have accelerated their efforts to mainstream tech diplomacy and started to train and employ dedicated specialists. In this regard, the US and Chinese approaches stand out for their scope. A paper by the Tony Blair Institute from 2022 states that “[t]he Department of International Cooperation in China’s Ministry of Technology employs around 140 tech diplomats, stationed in embassies across more than 50 countries, with a focus on North America, Europe and East Asia.” The same paper highlights that the US Coordinator for Cyber Issues, now replaced by the Bureau of Cyberspace and Digital Policy, employed more than 150 cyber policy officers, who were posted on diplomatic missions and regional bureaus worldwide.

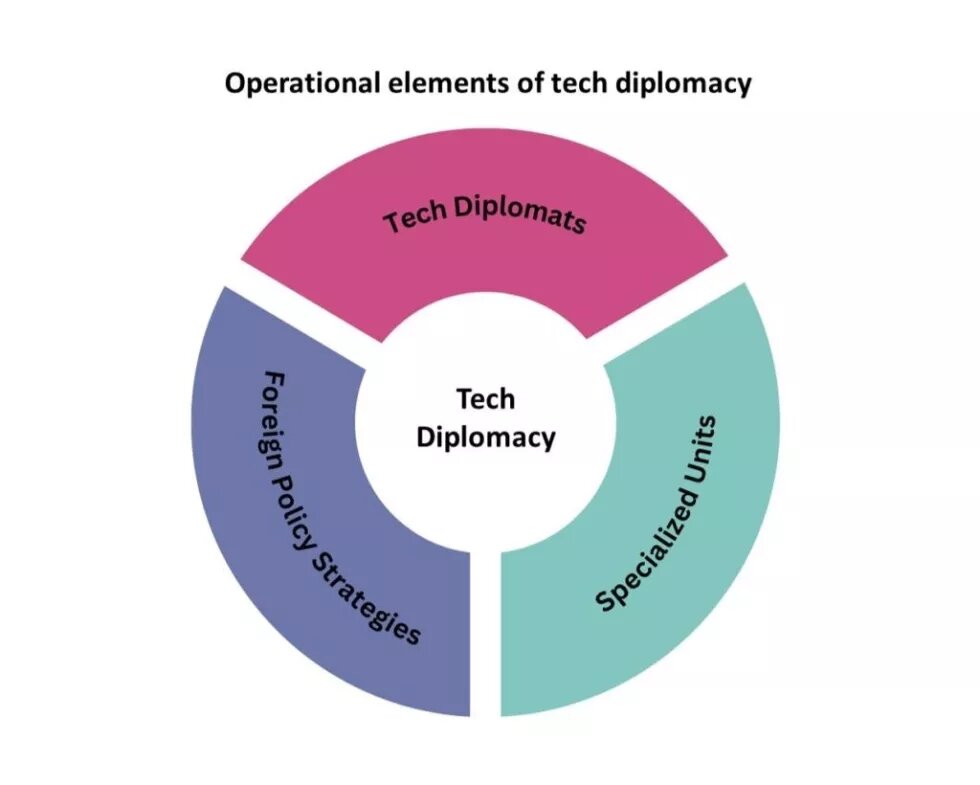

In addition to the appointment of dedicated personnel, governments across the world have created specialized units within their foreign ministries (as well as within other relevant ministries) and published comprehensive strategic publications that outline their approach to tech diplomacy.

TECH, DIGITAL, AND CYBER FOREIGN POLICY STRATEGIES

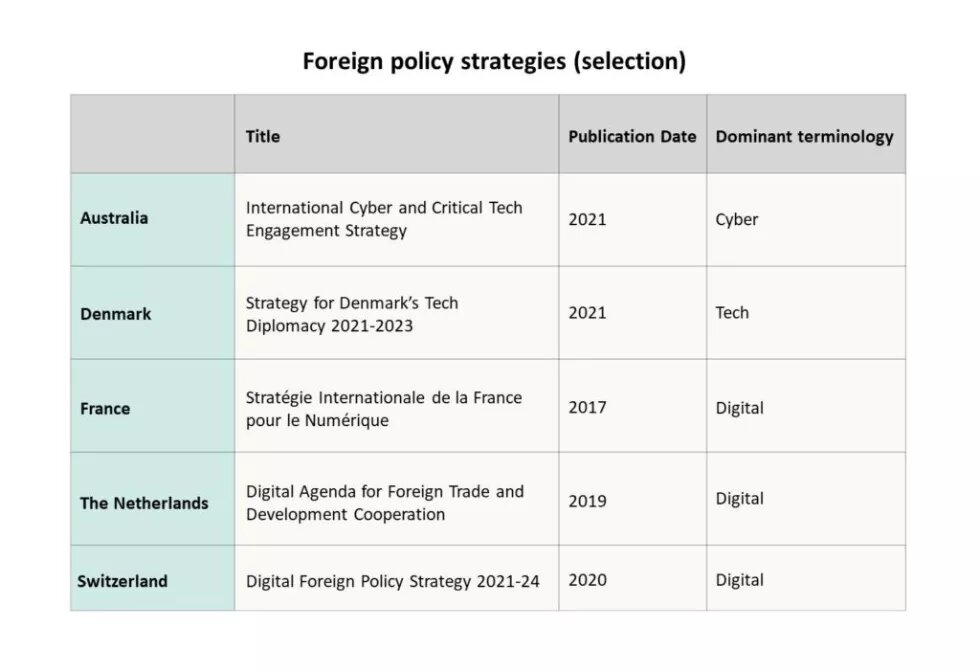

According to research conducted by the Tony Blair Institute, nine countries have developed foreign policy strategies dedicated to tech diplomacy. A possible definition for this type of foreign policy document could be “a strategy that outlines a country’s approach to digital issues and digitalization in relation to its foreign policy”, as suggested by DiploFoundation. Such tech diplomacy strategies touch on numerous digital issues and may connect the dots between the foreign ministry and various other ministries and key stakeholders. These strategies may also outline areas of policy priorities in regard to digitalization and how they ought to be pursued as part of the country’s overall foreign policy.

The existing tech-diplomacy strategies focus on issues of security and economic development and tend to also stress the topics of democracy and human rights. Some also refer to the issue of “values,” for example in terms of the societal responsibility of tech companies, such as the Danish strategy, or as a list of attributes such as the “vision of a free, open and secure digital space”, which is mentioned in the Swiss strategy.

A quantitative analysis of five of these strategies identified a notable difference in terminology used (see table below). For example, while the Danish strategy focuses on the qualifier “tech,” the Swiss strategy places the term “digital” at the center of its strategy, while the Australian strategy emphasizes the term “cyber.”

In light of this terminological variance, an academic paper from 2021 on The Era of Digital Foreign Policy concludes that “while the different strategies share a number of similarities and do touch on similar topics, they do not always speak the same language.” In some cases, different terms are used interchangeably; in other cases, differences in terminology reveal nuances in emphasis and focus.

This diversity in terminology can serve as a useful reminder that tech diplomacy is a recent addition to a growing set of terms that aim to capture changes in diplomacy driven by, or responding to digital technology. Other terms include: “Digital diplomacy,” “cyber diplomacy,” “e-diplomacy,” and “internet governance.” Different institutions, practitioners, and scholars tend to prefer different terms based on their respective institutional histories, or the wish to highlight particular aspects of a topic or practice. Nevertheless, there seems to be a general agreement that given its diverse interpretations, the term “tech diplomacy” may be seen as an umbrella term denoting an emerging field within diplomacy, which can be translated into varying practices.

NOT ON THE MAP (YET): TECH DIPLOMACY AND THE GLOBAL SOUTH

So far, national strategies on tech diplomacy have been published and pursued mainly by actors from the Global North – with the exception of China. The fact that many of the world’s countries, especially from the Global South, are lagging behind in developing dedicated national tech diplomacy strategies was prominently discussed at the 2022 UN General Assembly Science Summit. The debate highlighted concerns about the growing digital divide and missed opportunities to benefit from emerging technologies.

Despite the absence of official national strategies, countries of the Global South have begun promoting initiatives to drive forward tech diplomacy efforts. Thus, according to an article published on the global media development platform Devex, Brazil has engaged a dedicated tech diplomat in Silicon Valley, Pakistan is reported to have started “embedding tech into its foreign policy,” India’s foreign ministry has established a Division for New and Emerging Strategic Technologies, and Senegal is exploring various ways of engaging the tech industry, including the possibility of appointing a “digital ambassador.”

Indeed, given the numerous ways in which digital technology is relevant for economic development, countries from the Global South could benefit from the adoption of tech diplomacy practices. In addition, beginning to practice tech diplomacy in a timely fashion would help shift the balance in the norm-setting and regulatory debates shaping this emerging sphere, which is currently predominantly led and designed by countries of the Global North and China. Given that tech diplomacy also draws on discussions concerning democracy, human rights, and values in relation to digital technology, the absence of representatives from the Global South poses the risk that this realm will develop without taking these countries’ perspectives into account, thereby perpetuating and deepening existing socio-economic gaps.

BEYOND MULTISTAKEHOLDERISM

In 2003 and 2005, the two World Summits on the Information Society (WSIS) put digital topics on the global agenda. These two summits are thus often highlighted as the birthplace of multistakeholderism, a term that may be described as a way of meeting “constituencies who have a stake in (i.e. affect and/or are affected by) the challenge at hand.” In the context of WSIS and other internet governance processes, stakeholders include governments, international organizations, the business sector, and civil society.

In line with this approach, tech diplomacy focuses in particular, though not exclusively, on dialogue between governments and the tech sector. Thus, the UK tech envoy to the US, Joe White, described his work as consisting of “frank, future-facing exchanges with partners from across the U.S. tech ecosystem,” while Former Austrian Tech Ambassador, Martin Rauchbauer, and his colleague Clara Blume described tech diplomacy as a way of “mediat[ing] between governments and big tech” and institutionalizing “the relationship between the tech industry and governments by creating long-lasting relations and mechanisms that can be activated in times of crisis and need.”

Since the first WSIS forum took place in 2003, digital technologies have come to shape the economic and social realities of almost everyone on the planet to a degree that was hard to predict at the turn of the 21st century. Tech companies such as Amazon, Apple, Google, Meta, and Microsoft have not only generated enormous profits, but have also become dominant actors that shape economic and social realities. Danish tech ambassador Caspar Klynge, for example, described the big US tech companies as “de facto foreign policy actors,” and suggested to treat them as if they were state actors. This approach goes beyond the original idea behind multistakeholderism and reflects a shift in power dynamics between states and tech companies.

TECH DIPLOMACY: BROADER SHIFTS AND FUTURE OUTLOOK

The issues looming in the future of tech diplomacy aggregate around three main areas. First, currently, only a handful of countries are at the forefront of tech diplomacy. Over the coming years, many countries are expected to follow suit in implementing some, or all of the three operational elements of tech diplomacy, namely the training and appointment of dedicated personnel, the creation of specialized units within foreign and other ministries, and the publication of dedicated foreign policy strategies. This trend is expected to continue to pose a particular challenge to countries from the Global South. Lack of capacities, such as the limited number of tech diplomats representing countries from the global South, will perpetuate and exacerbate existing gaps. Therefore, concerns about a new or growing digital divide will remain relevant. Second, it remains to be seen to what extent multilateral approaches, such as the UN Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Technology and the EU’s Office in Silicon Valley, will be effective in contributing to and shaping global debates. Third, regulation and dialogue about values will remain important cornerstones of tech diplomacy. For example, the head of the EU’s Silicon Valley office, Gerard de Graaf, has asserted that “the EU does not have to justify itself for regulating the internet” and pointed out that recent EU regulation will require tech companies to make fundamental changes to their business models. With respect to digital norms, Austrian tech diplomats have been working on facilitating dialogue with the tech industry on the promotion of digital humanism.

Given the increasingly dominant role of the internet and other digital technologies in issues pertaining to security, economic growth, and the design of societies across the globe, the relevance of tech diplomacy, as an attempt to manage international relations, will only grow.

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of hbs Tel Aviv and/or its partners.