As dis- and misinformation continues to surge around the ongoing pandemic and the vaccines, citizens' trust in democratic institutions is constantly put to the test. This Spotlight explores the various factors that account for a country's level of resilience to mis- and disinformation via the prism of the Media Literacy Index (MLI) and integrates the case of Israel for the first time into the analysis.

Introduction

Faced with the Covid-19 pandemic, societies around the world witnessed a surge in fake news and conspiracy theories; tackling them became literally an issue of life and death. This challenge has been especially pertinent in democratic societies, where repressive measures can only have temporary duration or might even backfire, likely bringing about non-compliance and fostering distrust. The legitimacy of anti-Covid-19 measures depends on high levels of trust. The public’s trust must extend to authorities, who have to design and implement public policies, scientists and health workers who are on the first line of the defense, and journalists who have to report (or educate the public and hold authorities accountable) on this highly complex matter. The exponential growth in available news, information, and content about the pandemic — use and misuse alike–has been dubbed an “infodemic.”

The Covid-19-related fake news and conspiracy theories arrive on the heels of several years of increased misinformation. Indicatively, the so-called ‘post-truth’ phenomenon became Oxfords Dictionaries’ 2016 word of the year. Subsequently, the Media Literacy Index of the Open Society Institute-Sofia was launched in 2017 to measure the potential for resilience to ‘post-truth,’ ‘fake-news’ and their impact in a number of European countries.

Media Literacy Index: The Basics

The Index[i] is not an instrument for measuring media literacy itself, but rather, predictors of media literacy, with the aim of ranking societies according to their potential for resilience in the face of the post-truth phenomenon. The model employs several indicators that correspond to different aspects related to media literacy and the post-truth phenomenon. Level of education, state of the media, trust in society and the usage of new tools of participation are used as the predictors of media literacy. As they are of varying importance, the indicators are included with a corresponding weight determined by an expert panel as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Methodology of the Media Literacy Index:

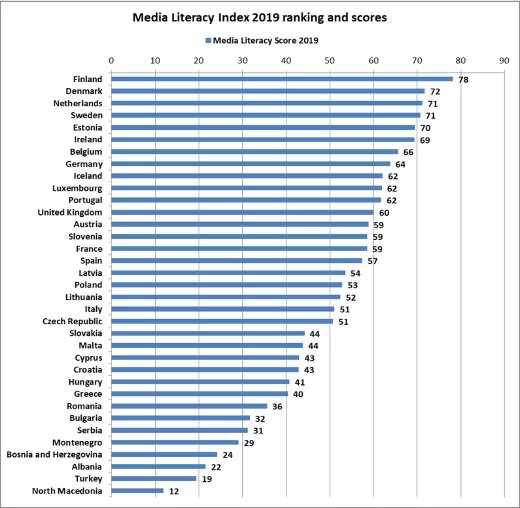

Finland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and Estonia top the Media Literacy Index 2019 ranking, shown in Figure 2. Finland, occupying first place among 35 countries, has a substantial lead over the rest with 78 points on a 0–100 scale. The last five countries in the ranking are North Macedonia (#35 with 12 points), Turkey (#34 with 19 points), Albania, BiH and Montenegro.

Figure 2: Media Literacy Index 2019 — Ranking and Scores:

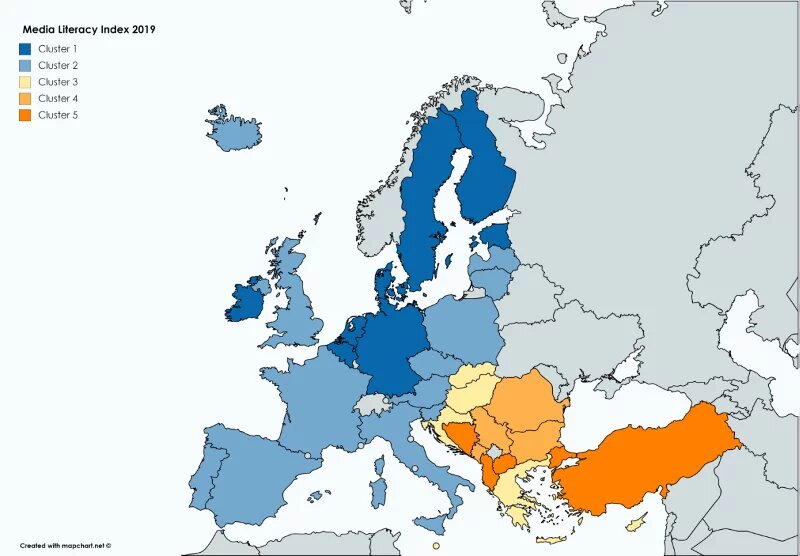

When the results of the cluster analysis are superimposed on the map (Figure 3), clear patterns emerge. The Northwestern and Western countries with the highest scores are the best performers, with the Southern and some CEE countries following closely. The countries with the worst scores are in Southeastern Europe, divided into the last and second-to-last cluster.

Figure 3. Map of Clusters in the Media Literacy Index 2019:

(Dis)trust and the Media Literacy Index

The Covid-19 crisis made trust in scientists, medical workers and journalists a necessity of the highest order. When the country scores in the Media Literacy Index are compared to the levels of distrust as measured by a public opinion poll, there are some predictably indicative findings. As this survey was conducted prior to the pandemic, it will be necessary to consider the pandemic’s impact once the immediate threat has subsided.

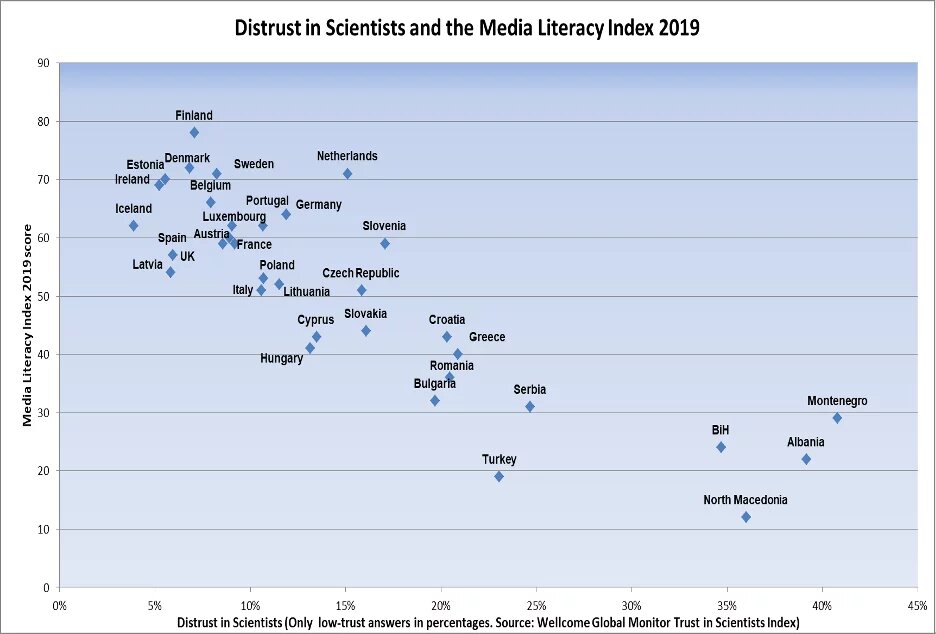

In order to examine the relationship between trust and the Media Literacy Index results the data from the recent Gallup Poll on the issue was compared to the Media Literacy scores (Figure 4). Countries with higher distrust in scientists have lower levels of media literacy, according to the results. Montenegro, Albania, North Macedonia and BiH, which have the highest level of distrust in scientists with over 25%, have among the lowest media scores. There seems to be a certain geographical pattern in these results. The other Southeast European countries (Serbia, Turkey, Greece, Romania, Croatia and Bulgaria) exhibit high levels of distrust in scientists –close to 20%-25% on average — and at the same time, low scores in media literacy. Finland, which is at the top of the ranking in the Media Literacy Index, has the lowest distrust in scientists. Denmark, Sweden, Estonia and the Netherlands follow Finland’s results closely.

Figure 4: Distrust in Scientists and the Media Literacy Index 2019:

Note: This scatter plot presents the Media Literacy Scores 2019 on the vertical axis (0 lowest to 100 highest) and the Distrust in Scientists in percentages on the horizontal axis (0% lowest and 100% highest). The “distrust in scientists” index includes only the percentage of “low trust” answers of the Welcome Global Monitor Trust in Scientists Index. Source: Gallup (2019) Welcome Global Monitor — First Wave Findings.

Distrust in the media has accompanied the rise in misinformation. The crisis in traditional media, related to the disruption of its business model, partly due to the rise of social media and its horizontal information streams, has hampered its ability to serve as gatekeepers of information and educate the public. In turn, lowered journalistic standards have begun to sever the relationship with the media’s audiences. In a number of countries, an additional set of problems relates to deliberate attempts on the part of elected officials to stifle media freedom with attacks on media or imposing direct control over the media in the form of censorship.

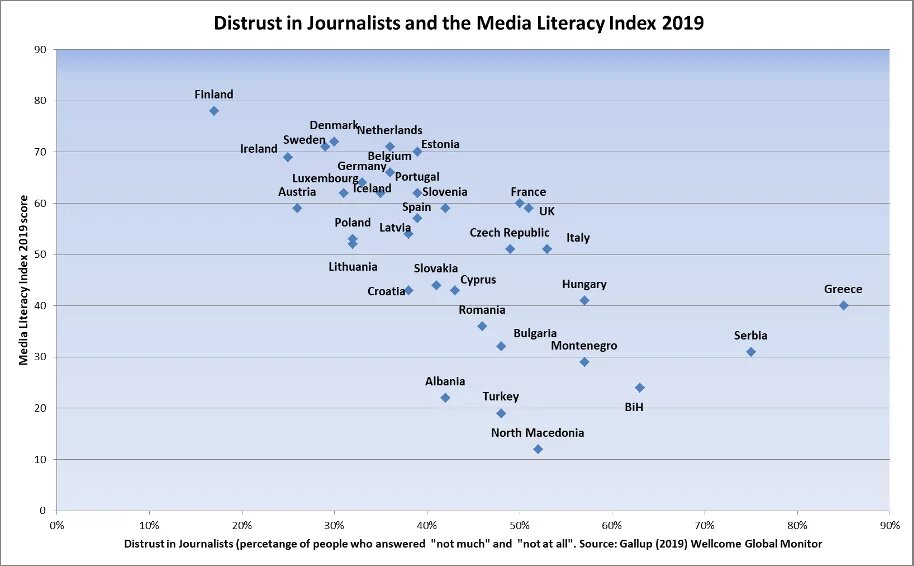

The scatterplot (Figure 5) shows the correlation between levels of distrust towards journalists and the media literacy index. The results show a certain pattern, as countries with high level of distrust in journalists generally have low scores in media literacy and vice versa. Finland is in a league of its own, with very low distrust in journalists — just 17% — and the highest Media Literacy Index 2019 score with 78 points. Greece has the highest level of distrust towards journalists, with 85% of those surveyed citing little or no trust. Serbia, BiH, Montenegro, Hungary and a number of other Southeast European countries also have low media literacy scores and very high distrust in journalists.

Figure 5. Distrust of Journalists and the Media Literacy Index 2019:

Note: The scatter plot presents the Media Literacy Scores 2019 on the vertical axis (0 lowest to 100 highest) and the “distrust in journalists” in percentages on the horizontal axis (0% lowest and 100% highest). The distrust in government is based on the combined percentages of the answers “not much” and “not at all” to the question “How much do you trust each of the following? How about journalists in this country? Do you trust them a lot, some, not much, or not at all?”. Source: Gallup (2019) Wellcome Global Monitor — First Wave Findings.

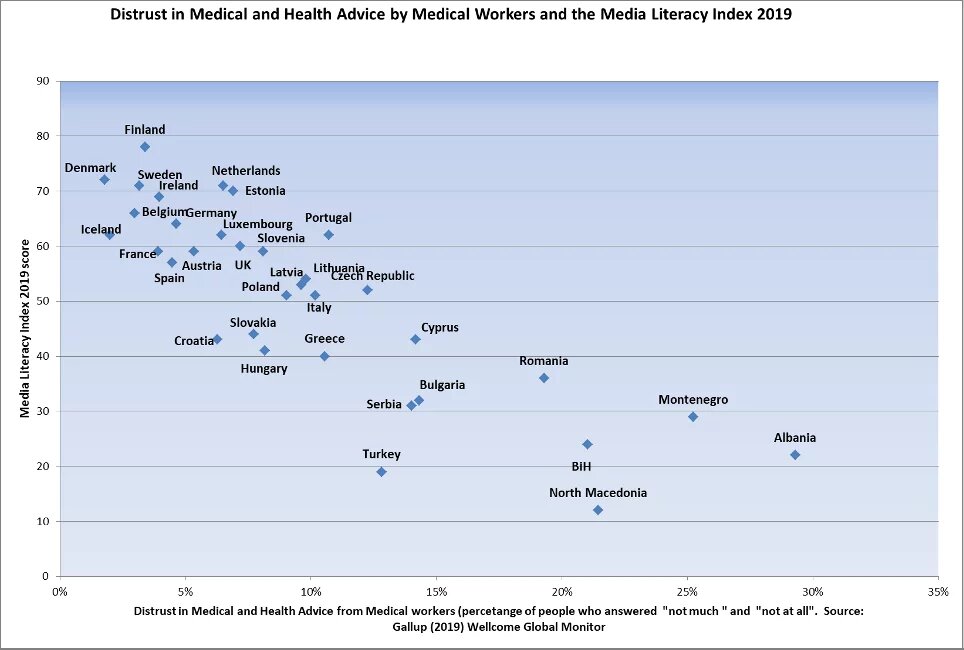

Figure 6. Distrust in Medical and Health Advice by Medical Workers and the Media Literacy Index:

Note: The scatter plot presents the Media Literacy Scores 2019 on the vertical axis (0 lowest to 100 highest) and the “distrust in advice from medical workers” in percentages on the horizontal axis (0% lowest and 100% highest). It is based on the combined percentages of “not much” and “not at all” in answer to the question “In general, how much do you trust medical and health advice from medical workers, such as doctors and nurses, in this country? A lot, some, not much, or not at all?”. Source: Gallup (2019) Wellcome Global Monitor — First Wave Findings.

As can be seen in Figure 6, low-performing countries in the Index generally register high levels of distrust in advice from doctors and nurses. Alternatively, top performing countries in the index have very low levels of distrust in medical advice from medical workers. The Covid-19 crisis brought to the fore the issue of trust in doctors and medical workers.

An Average European Joe: Where Does Israel Stand?

Israel is not included in the Media Literacy Index, but as the indicators and data used are publicly available, there is an opportunity to compare Israel to its European counterparts as long as the data is compatible.

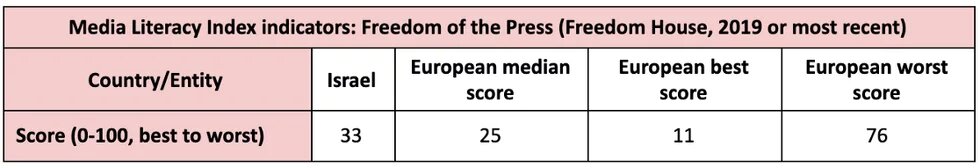

Figure 7: Freedom of the Press of Freedom House:

When the key indicators of the Media Literacy Index for media freedom and education are compared between the 35 countries already presented and Israel, we find that Israel is nestled somewhere in the middle with 33 points (Figure 7). The best performers among the 35 countries in the Index are Sweden and the Netherlands with 11 points each, while Turkey is last in the ranking with 76 points. This makes Israel comparable to such countries as Italy (31 points) and Poland (34 points).

Figure 8. Press Freedom Index of Reporters without Borders:

In another index for media freedom (Figure 8), the Press Freedom by Reporters without Borders (RSF), Israel scores 30.80 points (0 is best and 100 is worst), while the median score of the European countries in the index is 22.23 points. The best performer is Finland with 7.9 points, while Turkey is last in the ranking among the countries in the index with 52.81 points. Israel’s result makes it comparable to Hungary (30.44 points), which was highlighted as a problematic case in 2019 when the data was published leading to the issuing of a warning by the international fact-finding mission that the level of media control in Hungary was “unprecedented in an EU member state.”

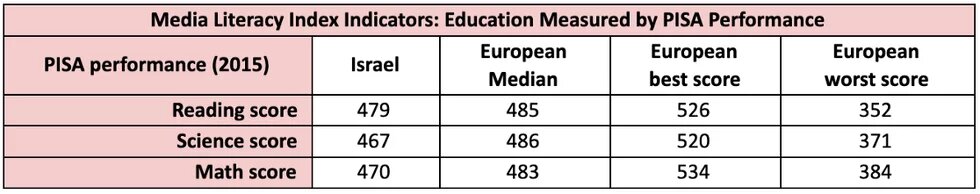

Figure 9: PISA Education Assessment:

The education indicators of the Media Literacy Index use the results of the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which is coordinated by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) on a regular basis. PISA provides an assessment of the quality of education in Reading, Science and Mathematics for the included countries.

Israel scores 479 points for “reading performance,” which is the most heavily weighted value in the Media Literacy Index. This places it close to the European average. In science performance, which has a lower weight in the Index, Israel has 467 points compared to the European median result of 486 points. In mathematics, which has a lower weight in the Index as well, Israel has 470 points compared to the European median result of 483 points.

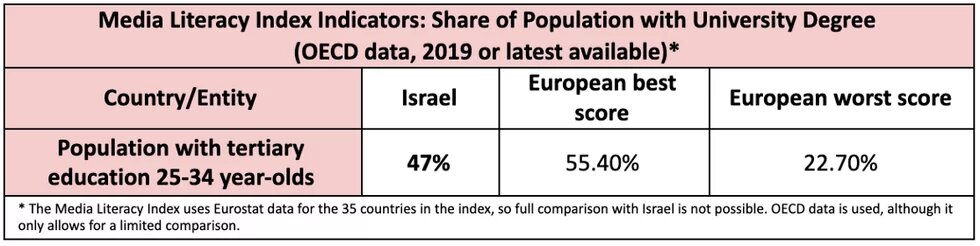

Figure 10: Population with University Degree:

The share of the population with a university degree is another education-related indicator used by the Media Literacy Index, but it is based on Eurostat data, so there is no data for Israel. However, OECD data allows for a limited comparison with the countries in the Index (see Figure 10). Israel’s share of 25–34 year-olds with tertiary education is 47%, while the European best result is 55.4% (Ireland) and the worst result is 22.7% (Italy). In this indicator, Israel closely aligns with Denmark, where 47.1% of people in this age group have a university education.

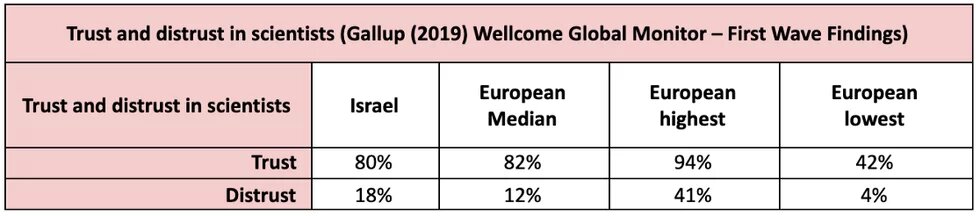

Figure 11: Trust and Distrust in Scientists:

Trust in scientists is another indicator where Israel and the countries in the Media Literacy Index were compared (Figure 11). The results indicate that 80% of Israelis place trust in scientists, which is close to the median European trust level. Iceland, with 94%, has the highest levels of trust in scientists, while Montenegro has the lowest, at 42%. On the other hand, levels of distrust in Israel 18% are closer to the European median result of 12%. Finland, the country with the highest level of trust in scientists, also demonstrates the lowest level of distrust. The same holds true for Montenegro, which demonstrates the highest level of distrust in scientists, at 41%.

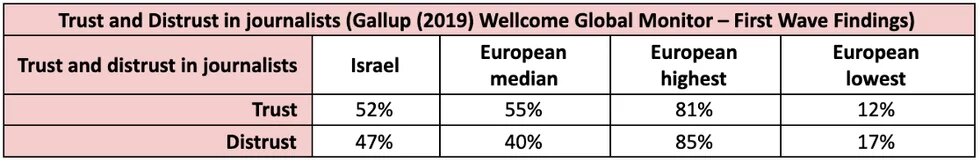

Figure 12: Trust and Distrust in journalists:

When the levels of trust and distrust to journalists are compared (see Figure 12), Israel is again close to the median results for the 35 European countries analyzed in the Index. Fifty-two percent of respondents in Israel said they trust journalists, which is close to the European median response of 55%. The distrust of journalists in Israel is at 47% compared to the European median result of 40%.

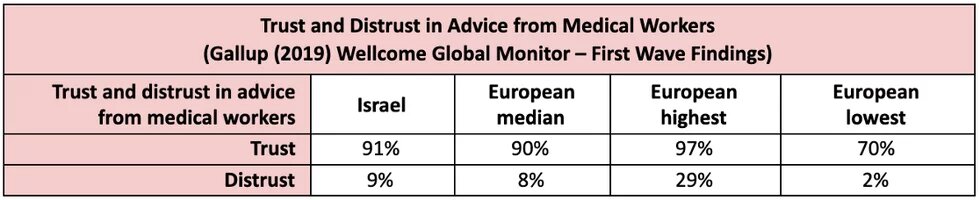

Figure 13: Trust and Distrust in Advice from Medical Workers:

Analysis of perceptions of medical and health advice from medical workers again puts Israel in the median (see Figure 13). The levels of trust in medical workers’ advice in Israel are 91% compared to the European median of 90%. The highest level of trust in the selected European countries is 97% (Belgium), while the lowest level of trust is 70% in (Montenegro and Albania). The level of distrust of medical workers’ advice is just 9% and is close to the European median result of 8%. The highest level of distrust in the European countries is 29% (Albania), while the lowest level of distrust is 2% and is registered in Denmark and Iceland.

The comparison between Israel and the 35 European countries shows that Israel would fall into the category of average and solid performers. The country’s results as a whole are close to the median results of the group of the 35 European countries included in the index. This is evident, as it is within the lines of the indicators of the Media Literacy Index (education and media freedom) as well as the key aspects of trust in societies as registered by the Gallup Poll.

Education before Regulation

The Media Literacy Index identifies what we believe are some of the fundamentals necessary for tackling dis- and misinformation: Highly-educated citizens, free and quality media and trust. There appears to be a link between levels of trust in scientists, journalists and advice from medical workers, and the Media Literacy Index performance. The better a country performs in the Index, the higher the trust levels. This observation seems to be especially relevant in the Covid-19 pandemic although cause-and-effect cannot be determined.

In the attempt to quash Covid-19-related fake news, many governments around the world — wittingly or unwittingly — impinged on media freedom. In many cases, according to the International Press Institute special monitoring tool: COVID-19: Number of Media Freedom Violations by Region, the pandemic was used just as a pretext. This again underscores the pertinent question of how to regulate fake news, disinformation and misinformation, with an eye to safeguarding freedom of the press. While regulation is certainly necessary, there should be checks and balances to uphold democratic values. In societies with fragile institutions or growing polarization, this might be a challenge. As the Media Literacy Index and the data about trust in the 35 European countries and Israel suggests, it may be preferable to tread carefully with regulatory approaches to dis- and misinformation and consider first investing in education and rebuilding public trust.

In a sense, media literacy can be compared to an inoculation to dis- and misinformation. It may not be 100% effective for everyone, but it is probably among the best solutions for society as a whole, mitigating the impact of disinformation and safeguarding against the worst side effects.

Close attention to media literacy is especially urgent against the backdrop of the vaccination efforts against Covid-19, which started in early 2021 as a main exit strategy out of the pandemic. The World Economic Forum listed four conditions necessary for vaccination efforts to be successful : Awareness, acceptance, accessibility and availability. Accessibility and availability relate mainly to technical issues of production and the logistics of delivering vaccines. Awareness and acceptance, on the other hand, have to do with the dangers of the infodemic and how to effectively address vaccine hesitancy and misinformation through communication campaigns.

Vaccine hesitancy is a complicated issue that does not have a simple explanation. In previous studies, such as that of the already quoted Gallup (2019) Wellcome Global Monitor — First Wave Findings, researchers point to the “declining vaccination coverage in Eastern Europe, where people are by far the least likely of any region to agree that vaccines are either ‘safe’ or ‘effective’,” citing an outside disinformation campaign as one of the possible reasons.

This means that countries with better performance in the Media Literacy Index will face fewer obstacles to carrying out their Covid-19 vaccination process. Early signs have showed that countries that meet all conditions — awareness, acceptance, accessibility and availability — are quite successful.

[i] The current article draws largely on the latest report from 2019 entitled “The Media Literacy Index 2019: Just Think about It,” available at https://osis.bg/?p=3356&lang=en , of the European Policies Initiative (EuPI) of the Open Society Institute — Sofia, which contains additional information on the methodology and data. In addition to the report, also available on the website www.osis.bg also are complete versions of the previous Media Literacy Index reports from 2017 and 2018.

The opinions expressed in this text are solely that of the author/s and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Heinrich Böll Stiftung Tel Aviv and/or its partners.